From Sanctuary to Alliance: Black Refugees Transform Seminole Resistance

Chapter 7: The African Roots of an 'Indian War'

Before Black History Month concludes, it is apt that this series gets to the crux of the Florida War because, as the U.S. Army General leading the campaign noted in 1836, “[t]his you may be assured, is a negro, not an Indian war….”

General T.S. Jesup was troubled by the effectiveness of black warriors and galled at what he saw as their outsized influence over Native American leaders to keep the war flames stoked.

But we’re not there yet. This series is still exploring the path to war. That requires discussion of its African roots.

We began in 1835 with Lt. William Maitland being ordered to Florida to hasten the removal of all Native Americans from the territory. But why did the U.S. want them removed?

Florida was an absolute backwater. The Spanish could do nothing with it for 235 years. The British tried for 20 more to no greater effect.

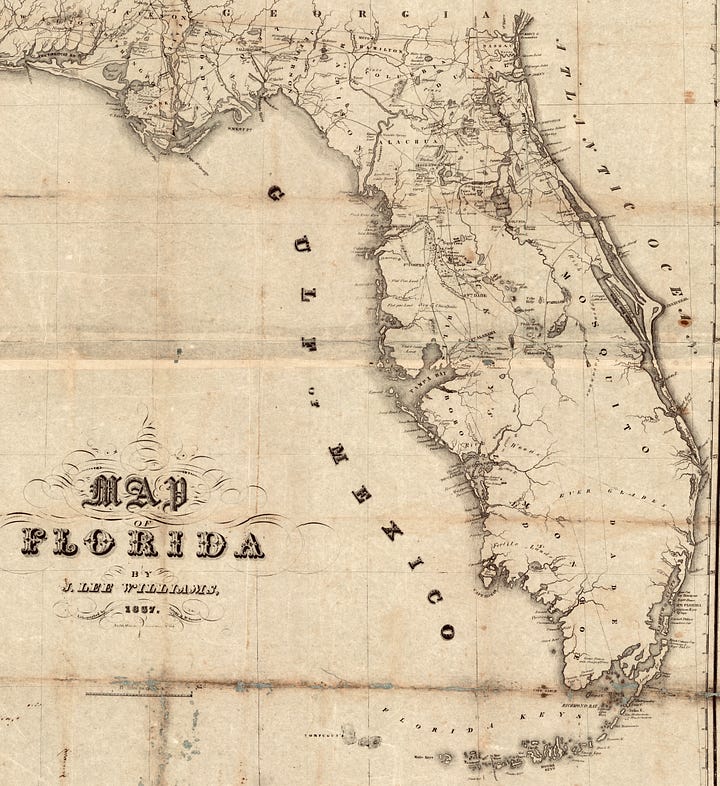

The American era began with little better prospect. In 1821, the U.S. acquired Florida from Spain and administered it as a territory. The few American population clusters were limited to the northern reaches where there was reasonably rich soil. But settlers had little interest in the vast bulk of the Florida peninsula. Everything south of present-day Ocala area was an unmapped wilderness of swamp and pine barren they felt was best left to the mosquitos and alligators.

So why was America so keen to expel the Native Americans who lived there?

Answer: the white people wanted to remove the Indian people because of the black people.

Florida: A Sanctuary from Slavery

Black freedom in Florida had been a thorn in Southern slaveholders’ sides stretching back to the British colonial days. In the 1700s, the Spanish, who then held Florida, offered freedom to defectors from Georgia and Carolina plantations if they’d come south across the border to help defend the city of St. Augustine. The Seminoles, too, offered safe harbor to those escaping American slavery.

Certainly both the Spanish and Seminoles maintained slave systems. But Spanish Florida also was home to free blacks and the slaves there enjoyed basic legal protections not afforded by the British and Americans. For its part, the Seminole slave system was more like vassalage: black people maintained personal and communal freedom so long as they made regular tributes of corn or cattle, or rendered services like blacksmithing and soldiering.

This made Florida an attractive option for black people considering relocation.

White Georgians and Carolinians chafed at this into the 1800s. It peeved slaveholders when their valuable “property” escaped south. But what really rattled them was the specter of black men under arms just across the border in Spanish Florida.

In the lead-up to the War of 1812 (rematch: America vs. Britain), the fear became acute. Americans worried that wild Florida, on which Spain had only the flimsiest grasp, would become a launchpad for international shenanigans. Worse, they feared black warriors would be the tip of the spear. Rumors swirled that Britain was drafting companies of Jamaican soldiers to garrison St. Augustine. Or was it black Cuban troops sponsored by Spain? American slaveholders north of the Florida/Georgia line shuddered at the effect this might have on those they held in bondage.

In 1812, the Governor of Georgia wrote breathlessly to U.S. Secretary of State James Monroe:

“[The Spanish in St. Augustine] have armed every able-bodied negro within their power, and they have also received from the Havana a reinforcement of nearly two companies of black troops! . . . . [I]f they are suffered to remain in the province, our southern country will soon be in a state of insurrection. . . . [This] is of vital importance to every [white] man in the southern states . . . .”

Georgia planters feared widespread slave revolt. Florida, the Georgia Governor demanded, must be tamed.

So Americans hatched a clandestine plot to take Florida from Spain. In 1812, Secretary Monroe’s envoy assembled a rabble army of Georgia frontiersmen and filibusterers. Under the protection of U.S. Navy gunboats, these “Patriots” invaded the Spanish port of Fernandina in northeast Florida. There, they declared themselves a “republic” and tried to rally disaffected Spanish subjects to their side. The idea was that the Patriots would call on the U.S. to formally intervene and liberate them from corrupt Spanish domination (hello Texas, Florida did it first!). While the invading Patriots and defecting locals looted swaths of northeast Florida, U.S. troops dug into a months-long siege of the city of St. Augustine to starve out the Spanish.

This off-the-books adventure — the “Patriot War” — bogged down immediately.

As the siege dragged on, the Spanish governor finally turned to the Alachua Seminoles — particularly Chief Bowlegs (Micco-Nuppa’s uncle) — for help. It was a big ask. The Seminoles and their Creek forebears had long been adept at playing one colonial power against the other (England, Spain, France, and the U.S.) for their own benefit. But now, for Bowlegs, the choice was stark. The Americans were at the gates. He knew that when the dust settled on this Patriot War, either Spain or America would have Florida. Which was better for the Seminoles?

The Seminoles had long experience with Spain as the distant, doddering old grandma who left them alone and occasionally sent gifts. America, by contrast, would be the violent, jealous boyfriend moving in. Bowlegs and the Spanish governor shook hands.

Soon, Seminole war parties began sacking Patriot-friendly plantations across what is now Duval, Nassau, Clay and St. Johns Counties in northeast Florida. This tipped the scales. The Seminoles pushed the Patriots to the very brink, blow by blow in guerrilla actions. Many Patriots fled to the coastal islands or back to Georgia.

Tangle at Twelve-Mile Swamp

Meanwhile, U.S. troops barely clung to their siege on St. Augustine. The massive Castillo de San Marcos — a stone fort with walls thirty feet high and as thick — was impregnable. The five-month standoff had achieved nothing. The city would not surrender. It was the American besiegers who suffered most. They were hungry, sick and dispirited.

When a relief ship finally arrived for them, a detachment of U.S. Marines and Patriots was selected to convoy a portion of the goods to an inland U.S. encampment. The convoy would have to pass through Twelve-Mile Swamp, an area known for recent grisly Seminole raids.

The nervous American detachment left late in the afternoon September 12, 1812, hoping that nightfall would hide them from the Seminoles. As it turned out, the Americans need not have worried about the Native war parties at all.

It was the black militia that caught them.

Juan Bautista (“Prince”) Witten, a black citizen of St. Augustine, had earlier led his company into the swamp to wait in ambush. Witten’s crew included 25 of the city’s free black militia plus 32 Seminole-allied blacks and six Seminole warriors. As the moon rose over Twelve-Mile Swamp, the U.S. convoy rolled into the trap. The first volley was withering. The second more so. The Marine captain fell (he died two weeks later) and another man was scalped in view of his compatriots.

Hours of close and mid-range combat took a toll on both sides. At midnight, Witten’s men burned one of the captured supply wagons and drove the other one off, carrying their own wounded back to the city. The devastated U.S. detachment huddled in the swamp until dawn when a rescue party arrived.

This fiasco at Twelve-Mile Swamp effectively ended the siege of St. Augustine. Diplomatically, the U.S. was forced to disavow its actions. It was, after all, officially not at war with Spain and hoped to keep her neutral in America’s newly declared war against Britain, the other War of 1812 (h/t to Prof. James Cusick; see references below). U.S. forces retreated back to bases they could hold while negotiating a peace with Spain. The Patriots followed them or straggled home to Georgia.

Witten’s black militia must have asked themselves the same question as Bowlegs’s Seminoles: would they fare better with the Spanish or the Americans? Witten’s people had experienced Spain’s qualified freedom. And looking across the border to Georgia, they could see the American offer of slavery and subjugation.

The answer for both the Seminoles and the black militia resulted in defeat for the American invasion of northeast Florida.

Seeking Revenge on the Alachua Seminoles

There is poetic justice that an expedition sent to crush black military power in Florida actually called it forth, polished it, and was crushed by it.

But there is disaster in the aftermath.

In the wake of Twelve-Mile Swamp, militia Col. Daniel Newnan gathered a crew of Georgians for a punitive expedition. His target: the Alachua Seminole towns some 80 miles west of St. Augustine, a four-day march. Shortly before the troops arrived at their objective, a Seminole war party stumbled into and engaged the Georgians near today’s Newnan’s Lake, east of Gainesville. Newnan’s men were pinned down for a week. They exhausted their provisions. As the Georgians turned to eating their own horses, the Seminoles continually sniped from the edge of rifle range.

At last, Newnan ordered retreat. The starving and the sick bore the stretchers of the wounded. Throughout the ordeal of their week-long flight, they were harried by the Seminoles. Finally, Newnan limped back to safety. Of the 117 who had followed him into battle, 16 were dead or missing and 9 were wounded. Newnan left Florida, never to return.

But there was little joy in it for the Seminoles. Their leader, the superannuated Payne, had fallen in battle. Far worse, Newnan’s defeat became an American cause célèbre. It inflamed white Southerners all the way to Tennessee. In fact, the Volunteer State drafted 250 of her sons to avenge the newly-famed Newnan. Georgia volunteers and federal troops filled out the rest of a new 550-man expedition that marched against Alachua in February 1813.

Bowlegs, who succeeded his fallen brother Payne as leader, was forewarned of this second invasion. As the Americans approached, Bowlegs oversaw the Seminoles’ hasty evacuation. The Americans arrived to find the Alachua towns deserted. So they burned them — Payne’s Town, Bowlegs’s town, and a Black Seminole town. Returning home, the Americans boasted they had burned nearly 400 homes and stolen 2,000 bushels of corn, 300 horses and 400 head of cattle.

After the ashes cooled, Bowlegs crept back to assess the destruction. There was no going home. All was gone. The area’s vulnerability was proved. Bowlegs moved his refugee Alachua people and black allies 40 miles west to the Suwannee valley. So ended the 70-year tenure of the Seminoles on the rich Alachua Prairie, the birthplace of their nation.

In their absence, the land was soon occupied by white settlers. Many brought enslaved black people to work their farms and plantations.

Florida: A Sanctuary for Enslavers?

Just 10 years after the Americans burned and looted the Alachua towns, things had changed dramatically. By treaty with Spain, the U.S. had acquired Florida, and by treaty with the Seminoles, the U.S. had established the wide Indian reservation over central Florida. The Alachua Prairie had become the center of territorial Alachua County.

But the friction over slavery had not diminished. For Americans, the Seminole reservation was manageable so long as only Seminoles lived there. But true to tradition, it remained a magnet for those escaping bondage. Slaveholders and bounty hunters persistently harassed the Seminoles for the return of fugitives or simply kidnapped blacks from their midst. Federal agents administering the reservation were consumed with navigating slavery disputes.

In 1834, the leading white men of Alachua County penned an urgent appeal to President Jackson:

“… Does a negro become tired of the service of his owner, he has only to flee to the Indian country, where he will find ample safety against pursuit…. [The Seminoles] have connived with, and, through the instrumentality of the negroes living among them, aided such slaves to select new and more secure places of refuge. There are, it is believed, more than 500 negroes residing with the Seminole Indians, four-fifths of whom are runaways, or descendants of runaways…. [I]t is evident that the absconding slave, who succeeds in reaching the Indian territory, is in absolute safety, and may laugh to scorn all exertions for his apprehension.”

Removal of the Indians was seen as the solution. This would spread Florida’s territorial jurisdiction over the entire peninsula, erasing the Seminole reservation as a sanctuary for escaped slaves.

That goal underpinned the 1832 Treaty of Payne’s Landing. But as of 1834 when the Alachua County slaveholders appealed to the President, it was clear the Seminoles and their black allies weren’t going anywhere.

Did the United States government take the matter seriously enough to resort to military force? After all, Florida was mostly wasteland, in itself not worth purchasing much less fighting over. So was the promotion of Southern slavery interests sufficient justification for war?

In the spring of 1835 as Lt. Maitland and hundreds of American soldiers were ordered to Florida for the Removal effort, it appeared the answer was yes. Still, the Americans hoped their show of force would awe the Seminoles into a voluntary mass deportation, averting bloodshed.

It was a miscalculation. The Americans would soon discover that the African desire for freedom was a force multiplier for the Seminole drive to keep their Florida land.

____________

References:

House Doc. No. 271, 24th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 30-33.

James G. Cusick, The Other War of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of Spanish East Florida, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2003.

J.H. Alexander, “The Ambush of Captain John Williams, U.S.M.C.: Failure of the East Florida Invasion, 1812-1813.” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 3, Jan. 1978.

I found this immensely interesting and logical. The truth will set us free!