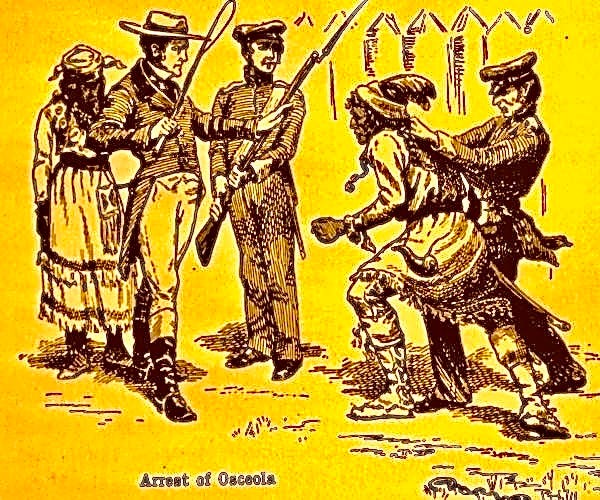

Osceola in Irons

Chapter 5: Wiley Thompson strikes again

In the previous post, with tensions high between Americans and Seminoles, the Agent Wiley Thompson had Osceola shackled and thrown in jail. For rudeness. Was it a tragic miscalculation or could it leverage the Removal?

Tustenuggee in the stir

Osceola sat in the dirt, his legs stretched out before him, back against the wall. He couldn’t cross his legs as he normally would, prevented by the iron cuffs around his ankles and the snake length of chain connecting them. His headcloth and long feather lay in his lap. He rubbed the stubble of his scalp. It was shaved but for a long-haired swath over his forehead and temples and two thin braids trailing over the crown and down the back of his neck.

He couldn’t draw a full breath. Not because the wooden bucket just out of reach in the corner held two days’ worth of his own waste. Not because the stale warm air, dim as the indirect light, didn’t move except under the wings of mosquitos and the bucket’s flies. It was because the walls of the room were a vice on his rib cage. Time was getting harder, not easier. He couldn’t focus a thought.

Osceola had suffered plenty of indignities in his life. In the last two years, many had come from the Agent Wiley Thompson. Since he arrived in the Seminoles’ country, proclaiming himself their great friend, the Agent had openly called them cowards and fools. Drunks and animals. Liars and old women. He parceled out their annual treaty payments like it was from his own personal pouch rather than just a pittance from what was rightfully theirs. He failed to give gifts showing respect when due.

But what Osceola couldn’t abide was the Agent’s incessant politicking, ever seeking to peel off one man against another. It was a poison Osceola had seen his whole life. It was what broke the Creek people where he was born. It had caused the slaughter of a thousand souls and made refugees of him and a thousand other survivors. If a people can be divided, they can be removed.

So Osceola had seen no great harm, indeed, he felt he owed it to the Agent that day in his office to remind him just where he was because he had evidently forgotten. He and all the bluejacket soldiers were temporary guests in Seminole country, suffered to remain on good behavior. But the more they trampled the rules the shorter would be their stay.

For this reminder, the Agent, not man enough to do it himself, had sent a team of soldiers to tackle and shackle and lock him in this airless hole. It was a grave insult. And the payback, one day, would be proportional.

But now Osceola really couldn’t breathe and he felt panic licking at the edges, icing his veins. What was the end-game? What would get him out of this? If only he could settle his racing mind and think.

He had it coming

Wiley sat in his office, replaying in his mind the biting disdain on Osceola’s face as he spat out what must have been a threat, or at least an insult. Osceola, peculiar among Seminole men, wore his long black ostrich plume stretching from the back of his turban rather than sprouting from the top. The Tustenuggee had been so rigid the billowy feather was still as an axe. Wiley couldn’t make out the Muskogee words, but he noticed Cudjo’s eyes widen before his gaze dropped to the ground, hoping the Agent wouldn’t ask for a translation.

Wiley didn’t. But he immediately shot to his feet and ordered Osceola from his office. The sneer never left the Tustenuggee’s face as he turned to leave. Even the long black plume mocked Wiley as it danced cockily in Osceola’s wake.

No, in retrospect Wiley was absolutely certain his course had been correct. Jailing Osceola for repeated insolence was the proper remedy. What else could he have done? The man had left him no choice. Now let him sit in irons and reflect on his actions.

Still, what was the end-game? Wiley was given to fits of temper, but he was also a man who needed a plan. And though he had been congratulated two days earlier on his bold order to imprison Osceola, the back-slapping from his compatriots had tapered into uncertainty. A gray pall had fallen over the entire fort. Where did it go from here? He couldn’t leave the Indian in irons forever. Insolence wasn’t a crime; if it were, Wiley would be running a prison camp. Very soon, the chiefs would come asking about their uncouth friend.

But Wiley couldn’t just set him free. If Osceola walked, it would be a show of Wiley’s weakness. No, America’s weakness. A reward for the insolence. It would come back to haunt. He knew, deep down, he had a wolf by the ear.

Wiley was in the right. Of that there could be no doubt. But what now?

Cudjo brings a stunning offer

“Boss, he sent me to tell you he’ll mark the paper.”

“What?” Quill in hand, Wiley Thompson looked up from the well-ordered stacks on his desk. Cudjo stood just inside the door. “Who will mark what paper?”

“You know, that paper, sir. The one says the other papers is good papers. Powell sends me to say he’ll do it.” Powell was the name the whites used for Osceola so Cudjo used it professionally.

Wiley looked at the interpreter blankly. The left side of Cudjo’s face was slack from a stroke some years back and he held his withered left arm at an odd angle, hanging his hat on it like it was a peg. Army officers called him King Cudjo, but not Wiley. First, he felt it was derisive. But moreover it was too familiar, could give him airs. Cudjo occupied a rare space around Fort King. He was free. The money he earned interpreting between whites and Natives went into his own pocket unlike the fort’s blacksmith whose wages fell mostly into his master’s. Wiley couldn’t bear Cudjo getting above himself.

“Powell will mark the paper?”

Unwilling to say it a third time, Cudjo nodded.

Wiley worked hard to keep the shock from his face. He never dreamed Osceola would sign that paper, the one acknowledging the treaties were valid. Micco-Nuppa and Jumper and other leading head men refused to do it, largely at Osceola’s urging. Yet now Osceola will sign? When no one asked? Unbelievable.

“Course, he goes free,” Cudjo put in, not sure the slack-jawed Agent was processing this.

He’d sign the paper. Which meant he agrees to go! To remove! To self-deport! With collapsing self-control and a smile hammering to get out, Wiley looked sternly back down at his desk. “That is all, Cudjo.”

“Sir . . . What I tell him?”

“That is all!”

With the interpreter gone, Wiley Thompson stood, beamed a toothy smile and clapped his hands together in triumph. The miracle he needed. The one he deserved! That embarrassing business about him trying to depose the five chiefs would be forgotten. Wiley sat back down and straightened his collar, then his mustache.

He began noodling how this would go down. He would need witnesses. Not just white ones. He imagined gathering a few friendly Natives, the two or three head men partial to emigration. Cudjo to interpret. They’d all go to Osceola’s putrid cell and pass him the paper through the door with an inked quill. While the prisoner’s X mark was drying, the blacksmith would strike off the leg irons and he’d be free to go. A handshake and no hard feelings.

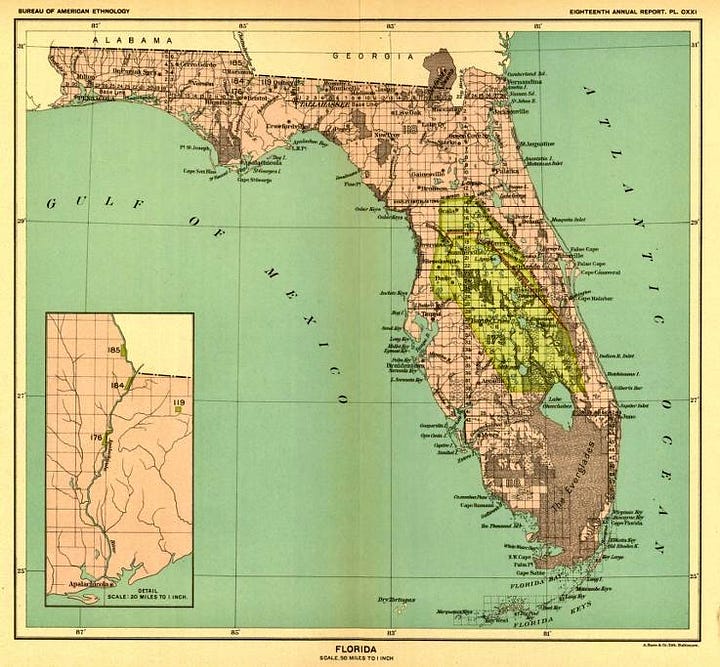

This X mark would change everything. Micco-Nuppa would see that his hardest warriors were meek as lambs and then the fat man could climb down off his ridiculous rejectionist pose like everybody knew he wanted to. He wouldn’t have Osceola prodding him into resistance anymore. In a matter of months, the whole Seminole nation would be peacefully escorted onto removal ships anchored in Tampa Bay, ready to sail off to Arkansas.

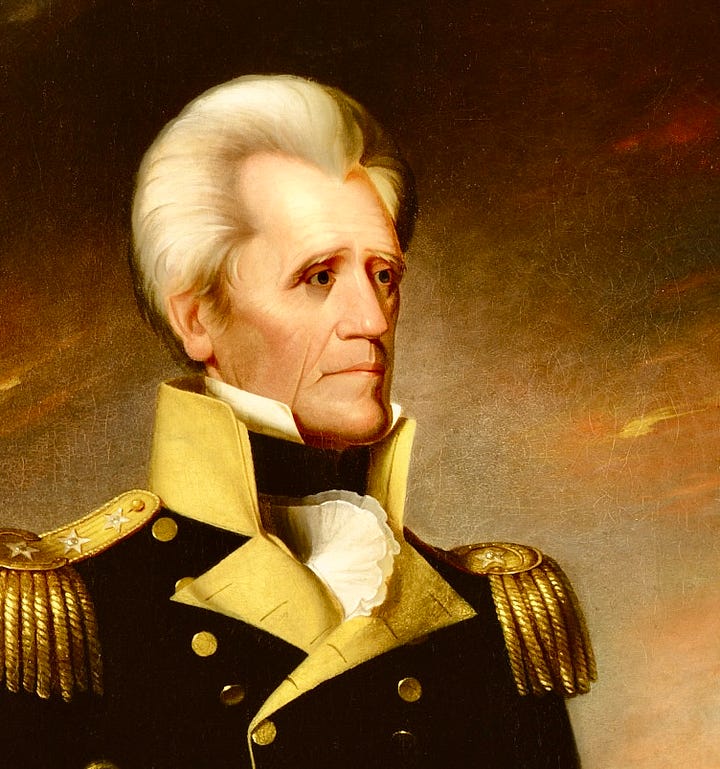

With what might pass for giddiness in Wiley, he imagined writing his glorious dispatch to the Secretary of War, massaged, of course, to be placed directly into the hands of the President, because it would be. And as he envisioned the look on that august lion Andrew Jackson’s face, reading aloud this report — because he wasn’t very good at reading — from his man in Florida, General Wiley Thompson, Wiley’s heart stopped.

Thought-bubble Andrew Jackson’s face screwed up as he crumpled the Agent’s report in a wiry claw. “Now that dull son-of-a-bitch is jailing Indians to extort their signatures?!”

The bubble popped. Wiley drew a handkerchief from his coat pocket and dabbed the cold sweat from his forehead.

He thought of the smug Seminole war chief sitting in a cell not fifty yards away. He remembered again Osceola’s sneer as he had sauntered out this very door just two days before.

Was Osceola playing him?

___________________

Sources:

Same as before, but this chapter falls under the heading of creative nonfiction.

Note on the image: ‘Arrest of Osceola.’ This image purports to depict an event in October 1837, but I would argue it is a more apt illustration of the events of this post in May 1835. I take the liberty because I have not found the real provenance of this image so its relation to 1837 could be erroneous. Several aspects are inconsistent with the 1837 date. In the 1837 event, Osceola, as a combatant, was ‘captured,’ not arrested. The 1837 event took place on a trail well south of St. Augustine, far from any buildings; but the image has a palisade palisade in the background, consistent with Fort King. In the 1837 event, Osceola was captured without resistance in the company of some 80 armed warriors and a like number of soldiers, while this image indicates Osceola was taken violently by a couple of soldiers, as was more nearly the case in May 1835.