The Florida War

Chapter 1: Maitland - what's in a name?

In 1492, Columbus threw a lasso that cinched together the peoples of the Atlantic continents: Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans. In Florida, some 340 years later, the action was still unfolding like nowhere else. The year was 1835. America began what it hoped was the final purge of all indigenous people from the Florida territory. The Seminoles made a stand to defend their land. Africans and their descendants who had escaped American slavery fought alongside them to remain free.

The result was America’s longest, deadliest, and costliest war against its indigenous people. It saw the largest slave liberation in American history by an order of magnitude. It’s one of the few ‘Indian wars’ where the Native people can declare a form of victory.

This is a story worth knowing.

And I’ve been absorbing it since I could read. It has much to tell us about not only about where we come from, but where we are now. The story is highly particular to the Atlantic world of Florida in the 19th century, but we see the sadly familiar patterns continue to play out around the world today.

What caught my imagination as a boy was the valiant struggle of a Native people against an unstoppable foe. Your basic cowboys and Indians stuff. But what keeps the older me fascinated is the personalities, the understandings and misunderstandings among white, black, and Native people fated to become combatants. The record is rich with this though it leaves plenty to the imagination.

As a lawyer, I’ve spent most of my career in the practice of federal Indian law. I also serve as the mayor of a city in central Florida. And I’m a history guy with an interest not just in Florida but in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, among other places. I’d like to think long exposure to and the study of law, politics, and culture has given me some perspective.

Once every two weeks in this space I’ll publish a piece on the Florida War, a.k.a. the Second Seminole War (1835-42). If you sign up with Substack you’ll get these automatically in your inbox. I’ll try to give the posts personal scale and impact and keep it engaging.

That said, let’s go.

Who Was Maitland?

As the mayor of Maitland here in the heart of Florida, I ought to know something about this city. Not just how many miles of road we re-pave every year or the cost of a sewer hookup or how many pickleball courts we lack, though those things are important. I mean the foundational stuff.

Like how did Maitland get its name?

The name is meaningful; it’s not an ad slogan like so many Florida towns (sorry, neighbors). It’s a clue to an incredible story. It connects directly to a turbulent upheaval that set the stage for us suburbanites. If you know how Maitland got its name, you’ll know infinitely more about us all, about the world.

I live almost two miles from Fort Maitland Park, which sits on the western edge of the pricey shores of Lake Maitland. (For those not from here, the park is 2.7 miles north of Orlando in central Florida.) The three-acre park serves mainly as a well-appointed public boat ramp. Lake Maitland is large and picturesque and linked to several other lakes through ferny canals traversed by ski boats and paddlers and the occasional alligator. Boathouses and mossy cypress trees ring the shores.

The city was named for Fort Maitland, which once occupied the area where the park now sits. The U.S. Army built the fort 186 years ago. It was a modest rectangle of 15-foot-long split pine logs pointed to the blue Florida sky. Maybe it had wooden blockhouses at two opposite corners for defense and cover from the elements. There’s no trace of the fort today. (Its actual footprint may have been where the condominium bordering the park on the south now stands.) It was abandoned to the humid mercies of the subtropical forest not long after it was built.

Well and good, but who was this Maitland guy they named the fort after way back in 1838?

He was William Seton Maitland, a New Yorker baptized at Trinity Church on Wall Street in 1798. That was six years before Alexander Hamilton was buried there. We know little about William Maitland but the bare facts. At 15, young William enrolled in the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. (A distant relative of mine, Rawlins Lowndes, was his classmate). Maitland was no world-beater, graduating 28th in a class of 30, but maybe he was having fun.

In 1820, Maitland was commissioned second lieutenant in the Third Regiment of Artillery. He served at posts in New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania, but also in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan, much of which was then on the American frontier, that is, the cutting edge where white people were chasing out Native people. Over the next eight years, Maitland slowly climbed to first lieutenant, the rank he held when he sailed into Tampa Bay in 1835.

This is where the story really begins.

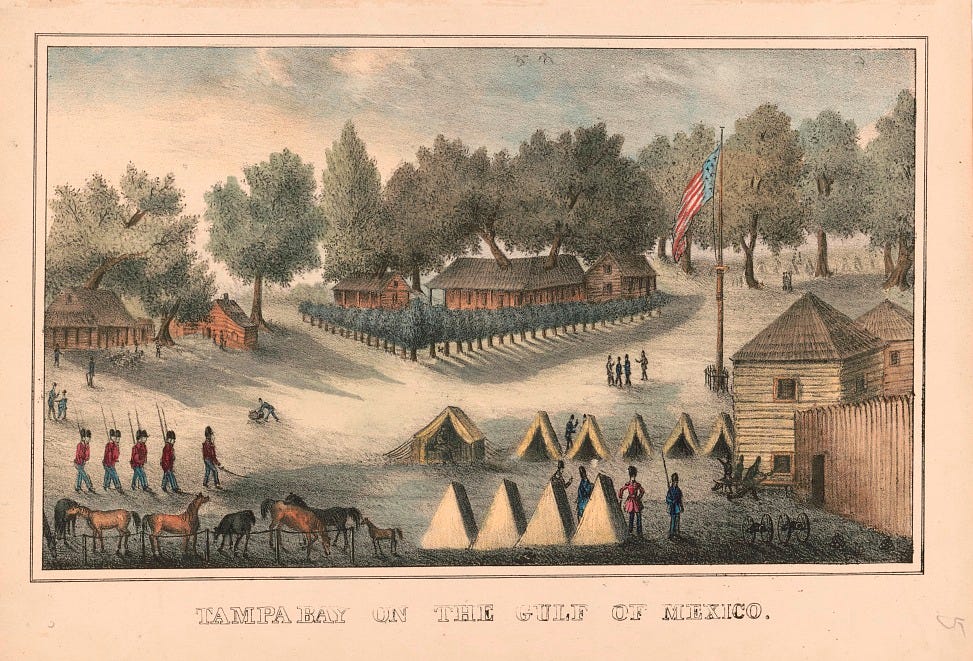

First, let’s appreciate that Florida back then was a wilderness. When William Maitland disembarked at Tampa Bay, there was hardly a settlement there at all and just a thinly staffed army outpost — Fort Brooke — on a rise where the Hillsborough River pours into the bay. Elsewhere, a handful of American settlements clung to the periphery of the territory: St. Augustine and satellite plantations on its northeast coast, Tallahassee 200 miles west in the Panhandle, Newnansville and Hog Town (now Gainesville) in between, and Key West some 350 miles south of that. All in, whites, free blacks, and enslaved people at these far-flung settlements, plantations, and farms totaled about 35,000.

The interior of the peninsula, the lion’s share of the territory, was governed by Native people and the Africans and African-descended people affiliated with them. These numbered maybe 6-8,000 spread through dozens of towns and villages like Okahumpka, Pilaklikaha, Chocochatti, and Buckra Woman’s Town. The huge Seminole reservation the U.S. had created in 1823 included most of Florida from just north of today’s Ocala south to a line even with the southern end of Tampa Bay (say, today’s Sebring). The reservation’s eastern boundary cut through swamps west of the St. Johns River; the western boundary lay 20 miles or so from the Gulf coast.

Estimating the total population of Florida generously then at 45,000 gives us the tiniest fraction of a fraction of the 23 million people who live here today. It’s an understatement to say that in 1835 people were few, and aside from small towns and plantations, very, very far between.

So why did Lt. Maitland sail into Tampa Bay in March 1835?

Maitland’s errand, bluntly, was ethnic cleansing.

Maitland wouldn’t have called it that. He would have said ‘removal.’ Not only is that more brutally efficient, it was the proper name of our nation’s policy. Lt. Maitland had come to Florida at the direction of his government to ensure that every Native American and affiliated black person was physically removed from the territory. The Indians were to be exiled to Oklahoma and the blacks mostly re-enslaved.

The Removal Act Congress passed in 1830 did not mandate Indian exile. It simply authorized the President to negotiate with Indian tribes throughout the country to “exchange” their ancestral lands for other land to be set aside in what is today eastern Oklahoma. The treaty-making process, 200 years old by that time, created legal fig leafs for whites to move Indians off their land, typically by bribery, trickery, or plain old threat of violence. But for land-hungry Americans in the 1820s, that rickety one-off process wasn’t moving fast enough. The Removal Act was meant to supercharge it. In the hands of Andrew Jackson — a man already responsible for the deaths of thousands of Native Americans in Georgia, Alabama and west Florida and the dislocation of thousands more — the Removal Act became a mass deportation order. Its result throughout the Southeastern U.S. was, colloquially and predictably, the Trail of Tears.

None of this was William Maitland’s fault. He was born into the world he was born into. The career he chose — at the height of the War of 1812 — provided steady work. Still, if he was digesting the news of the day as military men did, he had opinions about the rapid expansion of his young country at the expense of indigenous nations.

In any case, Lt. Maitland was minding his own business in early 1835, going on his fifth year of less-than-scintillating ordnance duty at a Pennsylvania army post, when he got the call.

Trouble was brewing in the wilds of Florida. No real violence had erupted yet, but the removal of Indians was not going as planned. In fact, it was going nowhere. So the U.S. Secretary of War, sitting in his Washington, D.C. office, hoped that a show of military muscle would intimidate the Seminoles, maybe provide the hint needed to avoid bloodshed.

Lieutenant Maitland received his orders. He was going south.

Next: Maitland goes in-country.

I chuckled at the dig regarding Maitland's name: "it’s not an ad slogan like so many Florida towns" ...

A great start to what looks like a fantastic romp into Florida history.