Maitland Goes In-Country

Chapter 2: Setting a stage for conflict

In the previous post it was the spring of 1835 and Lt. William Maitland was sailing to the edge of the Florida wilderness at Tampa Bay. Before landing him, let’s back up to find out who he was going to meet and why.

The First Seminole

With the Removal Act of 1830 in hand, President Andrew Jackson targeted Florida. He aimed to clear it of the people Americans called Seminoles as well as the black people allied with them.

Who were the Seminoles? There are many claims about where the word “Seminole” comes from. Depending on who you talk to it derives from the Spanish, or no, the Muskogee language. It means — pick one — outlaw, runaway, pioneer, or simply one who camps at a distant fire. The common theme is that it signifies a people apart.

Apart from whom? Apart from the Native American groups who controlled most of what is today Georgia and Alabama. But apart is not unrelated.

In the 1740s, a man called Ahaya led his Oconee people from the banks of the Chattahoochee River in west Georgia south onto Florida’s Alachua plain. They left behind the well-populated heartland of the Muskogees (a.k.a Creeks), which encompassed much of what is today Georgia and Alabama. It was not unusual for any of the dozens of Creek towns to move when corn fields were exhausted or conflict required. But the Oconees were among the first to seek a new place in peninsular Florida.

The Alachua plain was vacant, or nearly so, when Ahaya walked in. But it was haunted. North Florida had been the home of the Apalachee and Timucua people, who, as of 1600, were thicker even than the Muskogees to the north, numbering perhaps 50,000. But by 1705, they were all but gone, victims of the Spanish mission system. European diseases claimed large portions. Many were worked to death. Others were killed or carried off by English and Native (often Creek) slave raiders who sold them directly to Carolina planters or via traders to Caribbean plantations. Still others fled the area entirely.1 After two especially brutal assaults by the Carolinians and Native allies in 1704, Spanish officials ordered the abandonment of the mission provinces and withdrawal to the great stone walls of St. Augustine.

Ahaya would have known that story well. For 100 years, mission refugees had fled not just south to the central Florida hinterlands, but also north to live among the Creeks, or were hauled there as war booty. Over time, mission-phobic Apalachees established their own towns in Creek country and married into the highest levels of Creek society. The long, tragic arc of the Florida missions became part of Creek culture, too.

So Ahaya, a Creek migrant to Florida, knew who had been there before. He established his new town near the place the Timucua had called “Chua,” or sinkhole, probably for the great limestone sink in today’s Payne’s Prairie. In the mid-1600s, Spanish colonizers, with a captive Native workforce, began grazing cattle there and called it Rancho La Chua. Ahaya’s Oconee people, resident in the area since the 1740s, became the Alachuas or Alachua Seminoles, their land: Alachua or Elotchoway. And Ahaya became “Cowkeeper” to the whites because of his success as a cattle rancher.

A Philadelphia traveler visited Ahaya at Cuscowilla in 1774, some 30 years after the Oconee arrival, and described the founder of the Seminole dynasty:

The chief is a tall well made man, very affable and cheerful, about sixty years of age, his eyes lively and full of fire, his countenance manly and placid, yet ferocious, … his dress extremely simple, but his head trimmed and ornamented in the true Creek mode. He has been a great warrior, having then attending him as slaves, many Yamasee captives, taken by himself when young. They … waited upon him with signs of the most abject fear.2

Ahaya, or Cowkeeper, may have been the first of the 18th-century Creek migrants to peninsular Florida, but just barely. Others soon established towns in north and central Florida. The migration increased dramatically after 1814 as a result of the Redstick War in the Muskogee country. And just as mission Indians who had migrated north (voluntarily or not) mixed with Creek people, these southward-migrating Creeks mixed with Florida’s remaining Apalachees, Timucuas, Calusas and others who had escaped Spanish missions and dodged the incessant slave raids of the early 1700s. The Seminole nation was taking shape, having left the Creek confederacy like a young person leaving home but always intimately tied to it.

“Seminole” was a term of convenience for white people. It would have meant nothing to those it was first pinned on. They identified themselves by the Creek town they had migrated from (Tallassee or Eufaula, among many others), or that town’s mother town, or by the survivors of the ancient Florida people with whom they intermarried (Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa), or as Mikasukis of Chattahoochee River valley, or Yemassees driven from Carolina, or with the new towns they founded like Cuscowilla or Chocochatti. (One can imagine a Yankee clerk at a treaty negotiation, quill in hand, eyes glazing over five minutes after asking a Native man what ‘tribe’ he’s from. “Right, Seminole it is.”)

Maitland into Tampa Bay

President Andrew Jackson could tell with certainty who was a Seminole: any Native person within the borders of territorial Florida. And he wanted them all gone.

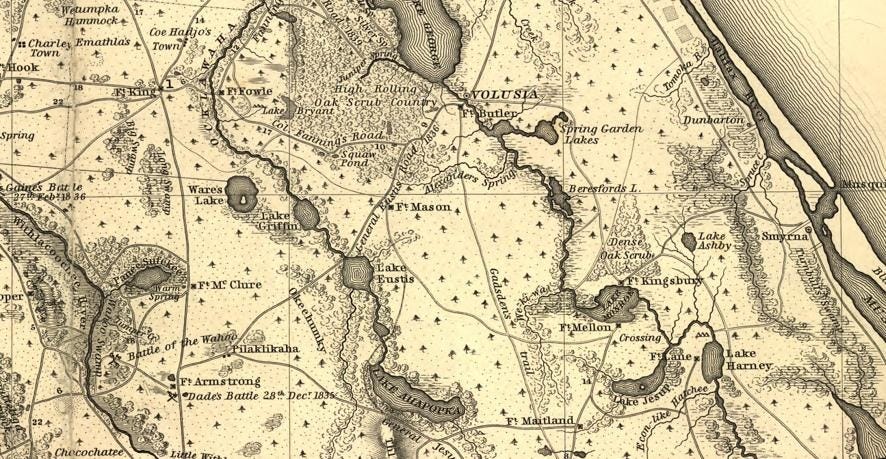

So in 1832, he dispatched his old friend James Gadsden (whose father gave us the ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ flag) to do the deal. Gadsden met a Seminole delegation in early May at Payne’s Landing near the confluence of the Ocklawaha and St. Johns Rivers (now underwater thanks to the U.S. Corps of Engineers and the Rodman Dam). The result was an ambiguous treaty apparently procured by bribery, by raw coercion or both. Seminole leaders later disavowed the treaty and even some American leaders quailed at it. But Gadsden’s job was done and he went home.

Then an odd thing happened. Nothing. The treaty languished, along with a subsequent bogus treaty, for a couple of years with no action on the ground. When the Americans again got serious about it in late 1834, they found Seminole attitudes had hardened against emigration.

Tensions in the territory rose sharply. No shots had yet been fired, but it was clear that the Seminoles wouldn’t go easily. That’s when, as noted in the previous post, the U.S. Secretary of War directed a show of military muscle.

Lieutenant Maitland answered the call. His job, along with the soldiers of ten companies also sailing into the Florida territory in early 1835, was to see the Seminoles off their land, peacefully if they would, violently if not.

Fresh off the boat in Tampa, Lt. Maitland marched his Third Artillery Regiment company 100 miles northeast through the Seminole reservation to Fort King in what is today Ocala. There, he had a front row seat at one of the dramatic preludes to the great conflict. What Maitland thought of this, we don’t know. If he was a letter writer or diary keeper, nothing has come to light. With no personal record, we see Maitland only in bureaucratic military dispatches recorded by others.

But as luck would have it, there was another soldier present at many of the places we know Maitland was, and this man was a prolific writer. We can use him as a stand-in for Maitland’s eyes and ears, if not his opinions.

Bemrose the Scrivener

This guy was John Bemrose, a teen runaway from England who, after landing in New York then walking to Philadelphia, presented himself to a U.S. Army recruiter. Bemrose was too short by regulation, just 5’7”, but the recruiter turned a blind eye when he learned the kid had been a druggist’s apprentice back home. A useful trade. Within a year, Private Bemrose was sailing for St. Augustine at the far reaches of the American empire. There he attached himself to an Army doctor and became a hospital steward. Bemrose was an entertaining writer and left us some of the best eyewitness accounts of this period. (Highly recommend An Englishman in the Seminole War by Randal Agostini, or join the Seminole Wars Foundation and they’ll send you a copy of Bemrose’s Reminiscences.)

Maitland and Bemrose were both at Fort King (Ocala) in March 1835, arriving from opposite directions. As noted, Maitland had marched 100 miles northeast from Tampa Bay. Bemrose had marched 100 miles southwest from St. Augustine on an arduous slog with wildly drunk and then terribly hungover soldiers. These movements boosted Fort King to somewhat more than 500 U.S. troops, adequate for the Secretary of War’s show of force. Over the next eight months, Fort King was the fulcrum of interaction between Seminoles and Americans. Maitland and Bemrose would have crossed paths often and perhaps were even friendly. If Maitland got sick (and everyone in Florida got sick), Bemrose, the hospital steward, would have cared for him.

Fort King was a military installation but it also housed the official Indian Agency, that is, it was the American administration center for the vast Seminole reservation in central Florida. “The duties of an Agent are to protect the Indian from the craft and encroachment of the Whites,” Bemrose noted. Here, the Agent contracted an armourer to repair the Indians’ rifles. Here, white settlers and bounty hunters came to complain that Indians were harboring blacks who had escaped slavery. Here also the Agent paid out the $5,000 annuity the U.S. owed the Seminoles for having taken north Florida from them. Finally, just outside the fort’s gates was the trading post, the sutler’s store. It was busy with soldiers and officers and settlers, but also Seminole people who came to barter skins and game meat for trade goods. Fort King in 1834-1835 was always alive with white, black, and Native people.

The Indian Agent was Wiley Thompson, a hard-edged former congressman from Georgia. President Jackson had appointed him after the Payne’s Landing treaty was signed, confident that General Thompson (his rank in the Georgia militia) was the right man to oversee the removal of the Seminoles.

In late March 1835, not long after Maitland and Bemrose arrived at Fort King, Agent Thompson convened the head men of the Seminole nation to read them the riot act. It wasn’t the first time. But now that Gen. Duncan Clinch had at his command a new show of blue-jacketed military might, Thompson hoped to make some headway with the Seminoles.

All the World’s a Stage

Within the fort’s barracks an elevated platform had been built, several feet high, to drill the troops away from the blistering sun or the pouring rain. On this stage, Thompson gathered Gen. Clinch and his phalanx of buttoned-down officers on one side. This probably included our Lt. Maitland. On the other side was seated the august Seminole delegation including Jumper, Holata Micco, Coa Hadjo, Charley Emathla and a number of lesser-ranked men. Spread below were 150 other Seminole men and a similar number of U.S. soldiers.

Crucially, this wasn’t just an Indian-white conference. The interface, the membrane through which communication flowed, was African. Cudjo made a living at the Agency interpreting between Seminoles and Americans. He had escaped enslavement by Americans and had lived for some time among the Seminoles. This gave Cudjo, who was African or African-descended, both languages, Muskogee and English, as well as some understanding of both cultures. Cudjo’s story was not unique. Hundreds of black people lived in the Seminole nation. Virtually all had escaped American slavery, or were born of parents who had.

Kicking off his meeting on this overstuffed stage, Agent Thompson rose and insisted on reading aloud a letter from “the Great Father,” President Andrew Jackson, telling the Seminoles why they must behave like obedient children, must honor the treaty, must leave their homes for the west or be forced to do so.

The Seminoles listened patiently to the lecture. As a rule, Seminoles prized diplomacy. Conflict in meetings was beneath them. So although they certainly bristled at Thompson’s directness, they deflected. Holata Micco rose for the nation. He said they would consider Jackson’s words and come back later with a reply.

This wouldn’t have satisfied Thompson, but neither did it satisfy Jumper, who rose next for the nation. Jumper, a.k.a. Huithli (or Ote) Emathla, was “Sense-Bearer” of the nation’s primary leader, the absent Micco-Nuppa (or Micanopy), and his brother-in-law to boot. Jumper was over 50, likely a veteran of the Muskogee Creek wars against U.S. troops under Jackson two decades earlier in Alabama and again in west Florida in 1818. He was tall, imposing, and, Americans said, exceptionally shrewd. Jumper faced the array of American officers and in tones less measured than Holata Micco’s — he had withstood other Thompson conferences and was weary of the harangue — let it be known that he was not disposed to leave his home. He sat back down. Cudjo duly interpreted Jumper’s words to the American side.

Bemrose reported the interaction:

“Tell him, Cudjo,” said [Agent Thompson], “if he breaks his word with us” at the same time pointing to Gen. Clinch, and the soldiers collected at the back, “I shall be obliged to call upon the White warrior to force him.”

[At this, Jumper sprang back up], spreading wide his arms, and standing in the graceful attitude, so easy to the savage, his eyes flashing fire, and his countenance at intervals taking a scornful look. Now and then he would burst into a derisive laugh!

“What’s he say, Cudjo?” was the agent’s query, excitement depicted upon his countenance.

“He say talk not to him of war! Is he a child that he fear it? No! He say when he buried the hatchet, he placed it deep in the earth with a heavy stone over it, but he say he can soon unearth it for the protection of his people. When he look upon the White man’s warriors, he’s sorry to injure them, but he cannot fear them, he had fought them before, he will do so again if his people say fight.”

Agent Thompson and Gen. Clinch stewed on this as Seminole leaders took turns with less provoking talk, reminding the Americans that threats and conflict were not the way but remaining firm that they had no intention of leaving their homes.

Before Thompson could speak again, the hand of God struck. With an uneasy wheeze then a thundering crack the timbers gave way, the stage collapsed.

Bemrose reported it this way:

The scene that ensued was most ludicrous. I could not help laughing to see fat and lusty Gen. Clinch, agent, officers, and Indians mixed up in a medley of humanity. The officers, and some of the Indians, took their sudden downfall in high glee. But there were other Indians, who did not fully comprehend the situation, and these rushed out from the supposed trap, screaming most awfully. On the reappearance of the agent, he quickly dispelled all fore-bodings . . . .

But the mood was broken and the Seminoles soon departed, telling Wiley Thompson they’d come back in a few weeks with an answer for him about emigration.

I’m willing to bet newly arrived Lt. Maitland was among the officers spilled from that collapsing stage. In any case, he was certainly a witness. For Maitland, after five years on ordnance duty in Pennsylvania, this was surely high drama.

It was only a taste of things to come.

Next: Have a little respect for Micco-Nuppa

Sources:

Randal Agostini, An Englishman in the Seminole War: A Memoir Based Upon the Letters of John Bemrose (Florida Historical Society, 2021).

William Bartram, Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc. NY, NY 1996). (First published Philadelphia, 1791.)

John Bemrose, Reminiscences of the Second Seminole War (University of Tampa Press, 2001).

James W. Covington, “Migration of the Seminoles into Florida, 1700-1820,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. XLVI, No. 4 (April 1968).

John H. Hann, Apalachee, The Land between the Rivers (LibraryPress@UF, Gainesville, Fla., reissued 2017).

Alfred J. Hanna, Fort Maitland: Its Origin and History (The Fort Maitland Committee, Maitland, Fla. 1936).

J. Anthony Paredes and Kenneth J. Plante, “A Reexamination of Creek Population Trends, 1738-1832,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal (6:3, 1983).

Kenneth W. Porter, “The Founder of the ‘Seminole Nation,’ Secoffee or Cowkeeper,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXVII, No. 4 (April 1949).

Clarence Simpson, Florida Place-Names of Indian Derivation. Florida Geological Survey, Special Publication No. 1 (1952, ed. Mark Boyd 1956).

John E. Worth, The Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida, Vol. 2: Resistance and Destruction (University Press of Florida, 1998).

Some insist the word Seminole derives from the Spanish word cimarron, meaning runaway or fugitive. The implication is that Oconees and others were fugitives from the Creek confederacy. Maybe. But we know for sure the Spanish used cimarron to describe Natives who fled the Spanish missions. Over the decades of the 17th century, such flights were chronic, depopulating the missions. To stem the flow, Spanish soldiers tried to hunt down these cimarrones. There are no records of how many cimarrones remained at large over time but, Florida being a big place with difficult terrain, it was likely significant. Perhaps it was the Alachuas and other Creeks intermarrying with these people that led to the Seminole label.

Bartram at 166. OK, William Bartram is more than a Philadelphia traveler. Let’s start with explorer, botanist, artist, anthropologist, political philosopher, expansive writer.