A Man Called Trout?

Chapter 8.5: Creek or Seminole: Will the Real Charley Emathla Please Stand Up

In the previous post, Charley Emathla had come to a sad conclusion — that he and his people must accept American terms and make the dangerous journey out of Florida for a distant reservation in the Arkansas territory. Despite Charley Emathla’s importance to Seminole and Florida history, he is a figure little known today. And much of what we do know is incorrect. This post aims to rectify that.

It is generally accepted that Charley Emathla was hardly a Seminole at all. Instead, he is reckoned as something of a carpetbagger — a Creek man only recently arrived from Georgia when he stumbled into the Seminole politics of Removal.

It was no less than J. Leitch Wright, Jr. (1929-1986), an eminent historian at Florida State University, who hung this erroneous tag on Charley. Wright’s groundbreaking book, “Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People” (1986), charts the complex relationships between Native Americans, European colonizers and African Americans in the Southeast over the course of centuries. Wright deftly wove together the international great power conflict that crashed through the region with the gritty detail of preachers, pirates, gentlemen, traders, traitors, filibusterers, maroons, slavers, kings, princesses, prophets and shamans. The tapestry Wright provided us is rich. It is foundational reading for anyone interested in Southeastern history generally or Native American history in particular.

But where Charley Emathla was concerned, it appears Wright was wrong.

To be fair, Wright prefaced his brief sketch of Charley Emathla by admitting, “[i]t is probably impossible to explain accurately his background and motivations.” But that didn’t stop him from trying.

Wright’s contention was that Charley Emathla had been a farmer in a Creek town near today’s Columbus in western Georgia. There Charley stayed until the late 1820s. For background, the 1810s and 1820s were a miserable time to be a Creek. Bloody wars convulsed the Muskogee country — a huge area encompassing the southwestern third of Georgia and the eastern half of Alabama. Andrew Jackson ran roughshod, forcing the broad and multi-ethnic Creek nation to surrender one great swath of their homeland after another. Professor Wright says that after Charley Emathla signed a treaty with the Americans giving up his Georgia land, he traipsed south into Florida with some followers and set up near Fort King at a place called Wetumpka. Wright dismisses Charley Emathla as an immigrant small-scale cattleman/farmer and “merely . . . a warrior of second rank.”

Not so fast.

First, we should know there were plenty of “Charleys” among Creeks and Seminoles at that time. Charley is likely not a Native name but an Anglo tag whites attached to Native men for ease of reference. Other common ones were Billy, Jim, Sam, Tom and John. Native men didn’t call themselves or each other by these names — they had their own — but these were useful when dealing with whites. (To be sure, Seminole and Creek people often adopted Anglo names in later years as the English language and American customs became more common among them.)

Second, we should know there were many more men called “Emathla,” which is a Native word. It is not so much a name as it is a title denoting civil authority. It was variously spelled Emarthlar, Emartla, Amathla, O’Mathla, Emotely, Imotely, Imala, etc. The variations owed less to the dialectical differences among the widespread Muskogee-speaking populations than to American recordkeepers trying to phonetically sound out what they were hearing from Creeks and Seminoles. Muskogee was not then a written language.1

(Other writers claim that “Charley” was an English approximation of the Muskogee word “Chalo” meaning trout. It was not uncommon for Seminole and Creek men to be named for iconic Southeastern animals like bear (nokose), panther (katcha), deer (etcho), or alligator (halpatter or hulbutta). But trout? Unlikely. Sounds more like an attempt to reverse engineer the name.)

So a person could be an emathla like one could be a doctor or engineer, but to distinguish him from other emathlas, whites might give him another name, too, say Charley or Billy. The point is that, statistically, the random conjoining of ‘Charley’ and ‘Emathla’ was bound to arise with some frequency. Nonetheless, Professor Wright found a Charley Emathla in the record and did not pause before confusing him with the man at the heart of this story.

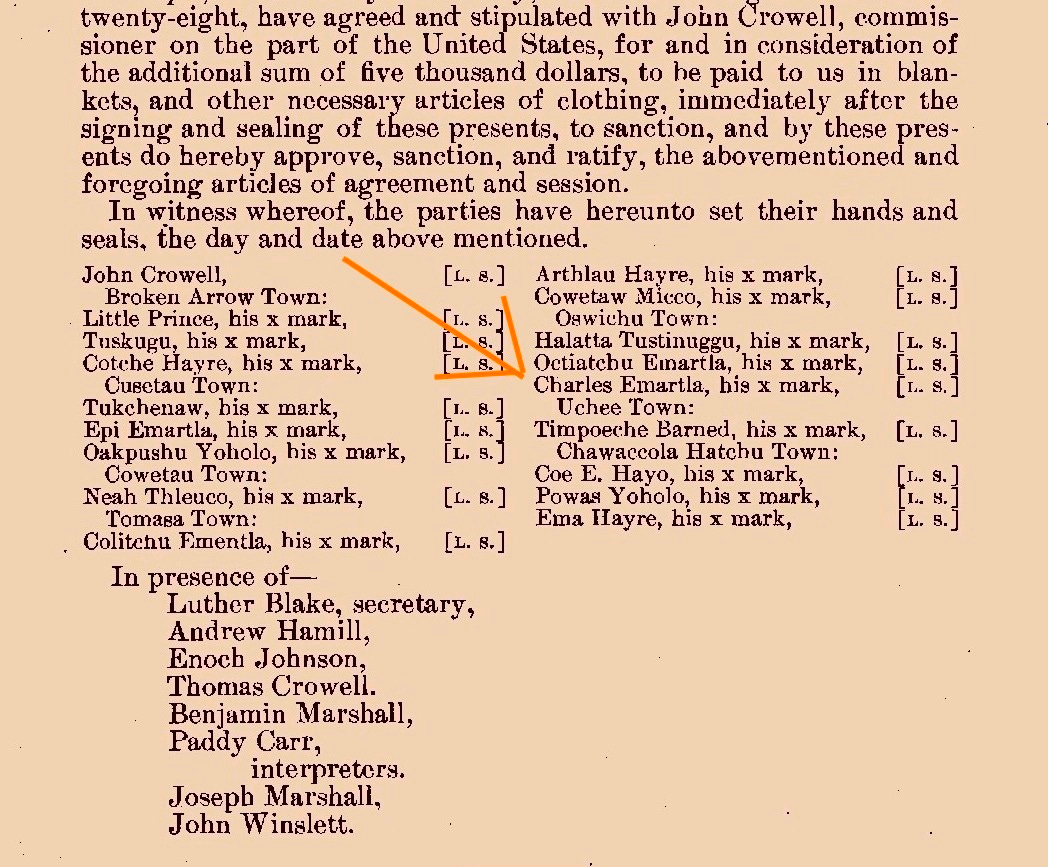

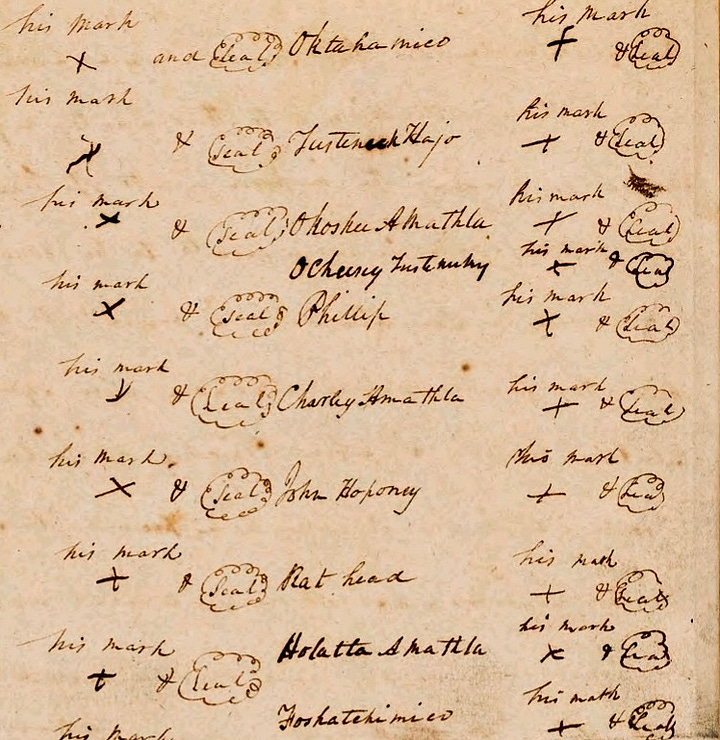

Professor Wright says that Charley Emathla, as a Creek, had signed the infamous Treaty of Indian Agency in Georgia in 1827. That treaty confirmed the cession of the very last acre of Creek land remaining in Georgia. It was the death knell of centuries of Creek tribal life there. Just 50 years earlier, almost all of Georgia had been under Creek control; in the years after the 1827 treaty, none would. This treaty indeed shows a Charles Emartla marking his X as a head man of Oswichu [sic] Town, Georgia.

Wright tells us correctly that in the wake of this 1827 treaty, choices for Georgia Creeks were limited. They could emigrate west across the Chattahoochee River and join their Muskogee kinsmen in Alabama (Creeks still controlled huge portions of that state), they could relocate to far northern Georgia and join the Cherokees, or move southeast to join the Seminoles in Florida. Charley Emathla, says Wright, chose this last option.

But did he? Aside from the similarity of names, Wright gives us no reason to believe that the Charley Emathla who surrendered the last of the Georgia lands is the same person who appears in the Seminole story. And further, it seems this Charley never migrated to Florida in any case.

Five years after the Treaty of Indian Agency, a Charley Emarthlar was still a head man of Oswichee Town on the Chattahoochee River. He was the head of a household that included three males, three females and two enslaved people, according to an exhaustive 1832 census of the Creek towns. (See below). It’s a safe bet this Charley and the one who signed the 1827 treaty were one and the same.

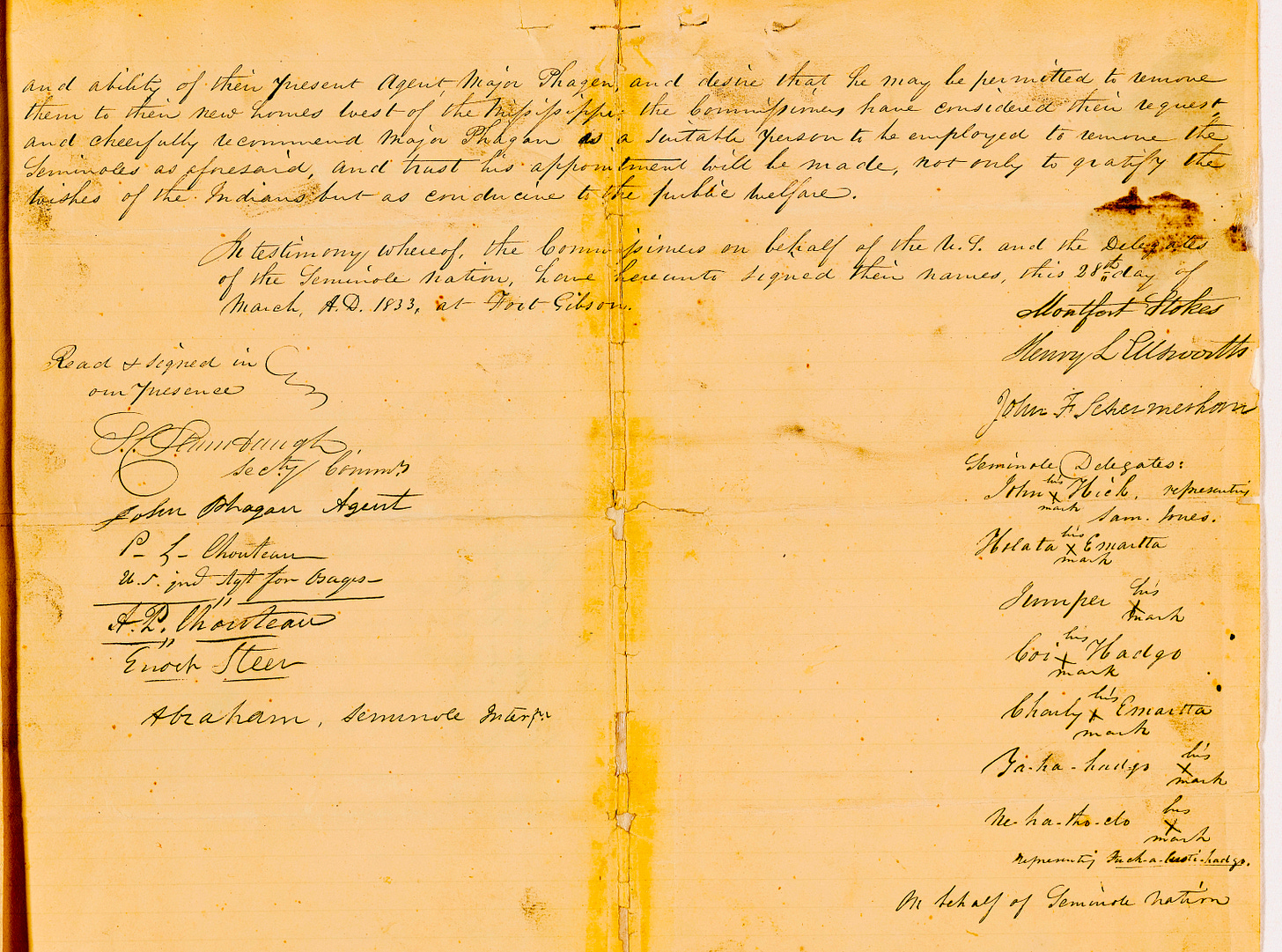

Now if Professor Wright’s Charley Emathla of 1827 was still in western Georgia or eastern Alabama answering the census as a Creek in 1832, how could he have been 350 miles away in central Florida signing a treaty as a first-rank Seminole chief at the same time? There is no doubt the Charley Emathla of our story made his mark on the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in Florida in May 1832. If Wright asks us to believe this is the same Charles Emarthlar of Oswichee, he asks too much.

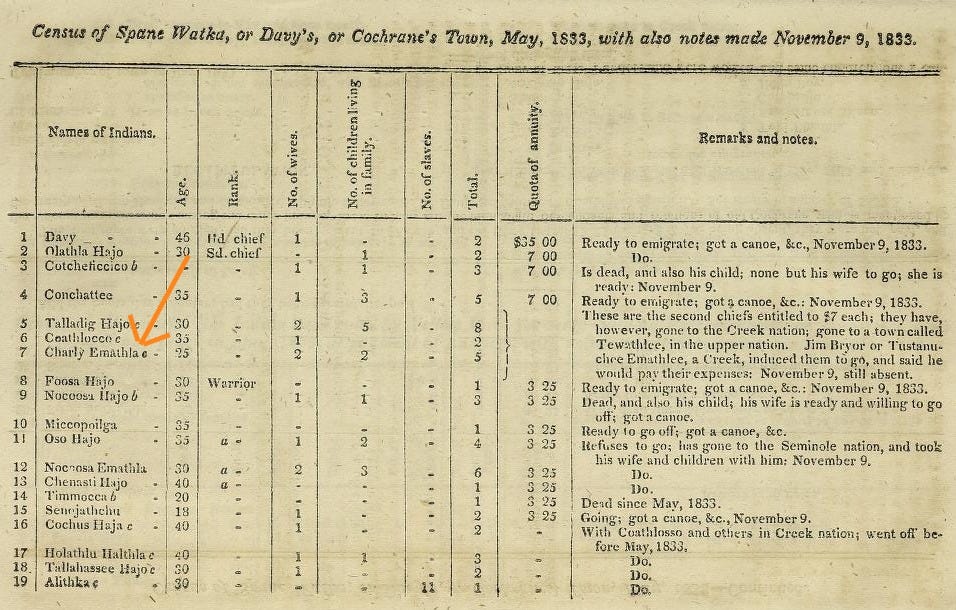

Interestingly, I found yet another Seminole/Creek Charley Emathla in the record. He was one of several “second chiefs” of Davy’s Town in west Florida on the Appalachicola River in 1833. This enterprising 25-year-old father of two and husband of two but slaveholder of none wasn’t actually present for the census because he had gone north into Alabama to try and stake a claim to land being parceled out to Creek people displaced by all the land cessions in Georgia. This, too, is not our guy. In May of ’33 our Charley Emathla was just returning to Florida from a disastrous journey to future Oklahoma where he had scouted land for the Seminole nation.

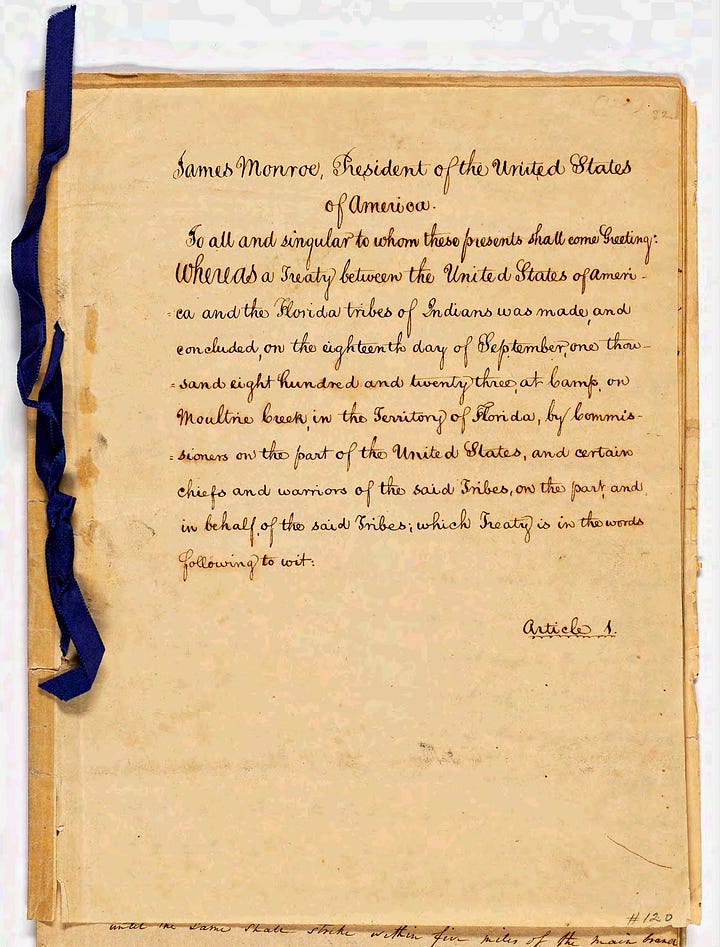

And closer to home, here’s another. A man called Charley Amathla had marked the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823, a critical moment for the Seminoles. But even this wasn’t our Charley, who, 11 years later at Wiley’s October 1834 conference and among men would know, said he had not attended the parley at Moultrie Creek, just south of St. Augustine.

This profusion of Charley Emathlas shows how viscerally connected the people of the Southeast were. The Florida War can’t really be understood except in the context of a half-century of Creek struggles. Leitch Wright succeeds in arguing that the distinction between Creeks and Seminoles on a personal or local level would have been all but meaningless. Many shared language, custom, and kinship ties. Think of a modern family reunion where some are fans of Alabama football and others go UF Gator. Where the distinction mattered was self-governance. Seminoles (with constituent Mikasuki and Uchee communities) bristled at the U.S. demand that upon Removal to Oklahoma they be folded into and ruled by a Creek nation composed of much larger former Georgia and Alabama Muskogee communities.

It could be that Charley had migrated to Florida from Georgia at some point. Many Creek people had, stretching back to the time of Ahaya, the founder of the Alachua dynasty (ca. 1750, see post here), on through the Florida War in the mid-1830s. Even if Charley didn’t hail from Creek country, it is likely his parents or grandparents did, as was the case with most of the people identified as Seminole in 1835. Their actions in Florida were informed not just by their Creek past, but the Creek present and future in Oklahoma which many were destined to share.

We will probably never know much more about him than what can be gleaned from American recollections of his speech and actions from May 1832 to November 1835. He was a serious man, highly regarded in the Seminole nation. Nothing speaks more clearly to this than that he was named to the select delegation of head men sent to scout the Arkansas territory. This delegation, in a very real sense, held the future of the Seminole nation in its hands. Would the nation have entrusted this charge to a second-rate newcomer?

As we’ll see in the next post, Seminole and Florida history may have been very different without Charley Emathla. This Charley Emathla.

We get a sense of the American/Muskogee interface from a census taker. “I have likewise spent particular pains upon the orthography of the Indian names, and in all instances used such letters in the spelling of them as would perfectly express their sound, dividing them into syllables according to their own mode of articulation, so as to insure, with ordinary attention, a proper, or at least an intelligible pronunciation. I have also avoided as much as possible, the repetition of the like names in the same town, and to this end have sometimes, with all the solemnity attendant on the ceremony, caused the individual publicly and by the proper authority, to be named anew. The name thus given is acknowledged by the party, and assumed as a war name, by which he is even afterwards known and recognized.” Excerpt of a letter from Maj. Thomas Abbot, U.S. Army, transmitting his census of the Creek nation to Lewis Cass, U.S. Secretary of War, May 1833. Senate Doc. 512, p. 236.