Ambush on the Trail

Chapter 9: Friendly Ghosts Catch Up to Charley

Previously, in Chapters 8 and 8.5, Seminole head man Charley Emathla reluctantly submitted to the prospect of Removal from Florida. As the deportation deadline draws closer, Charley’s enemies become more desperate.

When the shriek broke the stillness, Charley Emathla braced for impact. He recognized the voice before he turned to see the eyes of the man at the other end of the rifle barrel.

Charley Emathla expected the encounter. The warnings had been clear. But maybe Charley was surprised that this would be the man to step forward as his executioner. After all, Charley had saved his neck once, had counted him as an ally. But maybe on reflection — and he had precious little time, for only a moment was given between the war whoop and the first bullet — Charley knew that Osceola would not miss the opportunity.

Not six months earlier, Charley Emathla had considered their argument settled. Osceola had swung to Charley’s side in spectacular fashion. All it took was a brief stint in an American jail to convince him. When Osceola emerged, he had summoned all his friends and relatives to witness his humbling before the U.S. Indian Agent, Wiley Thompson. Osceola took up the inked quill and marked his X on a paper submitting to Removal as Charley Emathla looked on.

It was a stunning reversal. Till that moment in June 1835, Osceola had been the most ardent enemy of the American demand for Removal. His quick conversion was so extraordinary that perhaps, in retrospect, it should have been questioned. Maybe Charley Emathla, an experienced and thoughtful man, had harbored doubts. If not about Osceola’s sincerity, then at least about the younger man’s steadiness.

But this day in late November 1835, on the sandy trail between Emathla’s Town and Fort King, Charley was in no doubt of Osceola’s intent. This time Osceola meant to mark it with blood.

Contemporary American accounts of this showdown put Osceola’s actions down to low treachery, cold ambition or hot blood thirst. There may truth to each, but they miss the larger picture.

As Charley Emathla faced Osceola, both men understood their confrontation in a broader context — the rumbling of a distant earthquake.

Red Stick Refugee

Florida wasn’t Osceola’s home to begin with. He had come, as a boy, from the Muskogee heartland in Alabama. He was born about 1804 in Tallassee town, part of the vast and vibrant Muskogee (Creek) confederacy that encompassed the western half of Georgia and most of Alabama. The Muskogees were not novices at dealing with whites. They had been trading with, fighting, marrying, and generally abiding the French, English and Spanish for some 250 years. But Osceola’s youth coincided with an accelerating threat: land-hungry Americans were carving off chunks of the Muskogee country and pressing through the borders as never before.

In response, a Nativist movement — called the Red Sticks for their painted war clubs — grew among the Muskogees. The Red Sticks had accepted the warning delivered in September 1811 by the renowned and peripatetic Shawnee diplomat/war chief Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, Tenskwatawa. A day was coming when whites would overrun the Muskogee country, or worse, when the Muskogees would lose their way and become as whites themselves. The only hope was the formation of a pan-Indian unity — northern nations combining with the southern — and the purification of society by purging all things American.

Tecumseh and his Shawnee delegation delivered their orations at Tuckabatchee during the huge annual meeting of the Upper Towns of the Muskogee confederacy. Thousands attended. Osceola may have been too young, but his uncles and cousins would have been there, their towns being just a few miles distant. The message was amplified throughout the country.

Tecumseh’s mission south to the Muskogees was stamped with divine authority. After he returned home to Indiana, massive earthquakes shook the region. The New Madrid quakes from December 1811 to February 1812 included the greatest ever recorded east of the Rockies. Centered in the Mississippi River valley, they were so violent they reversed the flow of the great river briefly. Tremors were felt from Canada to New Orleans to Charleston and were said to have rung a Boston church bell.

The Muskogee country shuddered. Hadn’t Tecumseh, with his access to supernatural powers, told them he would send a sign by stamping his foot three times? Roiled by Tecumseh or not, the earth was reporting a deep cosmological imbalance which the Red Sticks were called to answer.

But the Red Stick target wasn’t whites per se; it was fellow Muskogees, the “friendly chiefs” who had long accommodated white culture and commerce. In 1813, following the murders of a number of white settlers by some Muskogees in the borderlands, American authorities demanded justice. Friendly Muskogee chiefs supplied it, hunting down the guilty, whipping some and executing others. Red Stick anger boiled over at this. With religious fervor, they demanded justice of their own. Their trickling campaign of assassinating friendly chiefs roared into a waterfall.

The “peace party” fled as the Red Sticks overtook town after town demanding fealty and threatening those who opposed them. The spreading rebellion drew a furious response from powerful chiefs. White settlers within or on the perimeter of the Muskogee country feared for their lives.

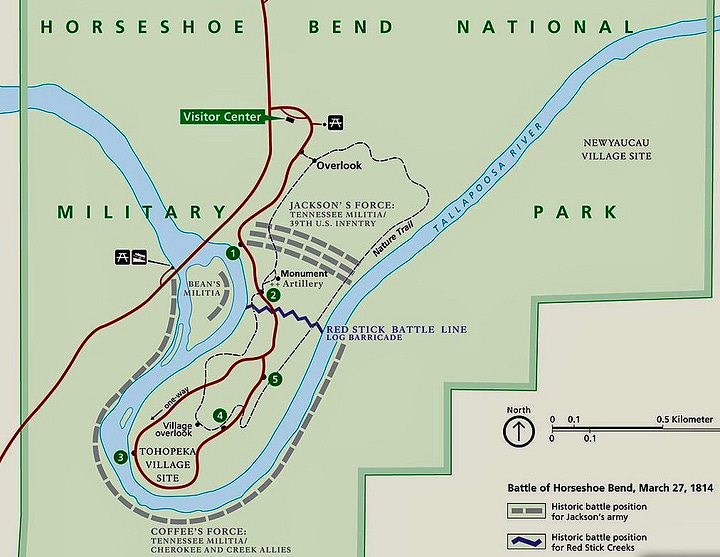

What began as a Muskogee civil war quickly became a war of American conquest. Coming in on the side of the friendly chiefs, U.S. Major General Andrew Jackson shattered the Red Sticks at the 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama. With an estimated 800-900 warriors slain, not counting the women and children encamped at the Bend, it was perhaps the bloodiest day for Native American fighters in the 200-year chronicle of America’s ‘Indian wars.’ (This Two Egg TV video recounts the battle.)1

In the chaotic aftermath, many Red Sticks fled the Muskogee country, including the family of Osceola who was then just a 10-year-old boy. But even the “friendly” Muskogees suffered. Jackson quickly forced his allies into the Treaty of Fort Jackson by which they surrendered 22 million acres of Muskogee land: roughly the southern fifth of Georgia and half of Alabama.

The Red Stick War, also called the Creek War, precipitated the end of the Muskogee confederacy in the ancient Southeastern homeland and its Removal west of the Mississippi.

But the war also shaped the emerging Seminole nation. So many refugees fled south to Spanish Florida that Muskogee became the dominant language, eclipsing the Hitchiti spoken by the Alachuas and the related tongue of the Mikasukis. The so-called First Seminole War soon followed (1817-18) as Gen. Jackson and his “friendly” Creek allies invaded north Florida in pursuit of former Red Sticks and those who harbored them. The result was to push many of these native and black communities into (or back into) the central part of the Florida peninsula where they continued their amalgamation into the Seminole nation.

The Red Stick War: Lessons Learned

Southeastern people all drew lessons from this catastrophe.

Charley Emathla would have been in his late 20s or early 30s during the Red Stick War, prime fighting age. If indeed he was an emigrant from the Muskogee country (see previous post),2 he would certainly have seen action in that war. In any case he would have listened to bitter tales of the Red Stick War beside hundreds of fires over the years. When he came to be the leader of a Seminole town in his 50s, Charley Emathla concluded it would be suicidal to go to war against the Americans. They had smashed the great Muskogee confederacy; what chance did the smaller, disorganized Seminole nation have? Charley felt the only option was to sell his cattle and swap his Florida situation for one in distant Arkansas.

Osceola, whose young life was entirely shaped by the Red Stick War, drew a far different conclusion. It had been the schism among the Muskogees that had crippled that nation, leaving it weak and exposed to Andrew Jackson’s coup de grâce. Had the Red Sticks redeemed their compromised nation by uniting it under their leadership, they would have whipped Jackson’s army or would have been so clearly invincible that the Americans would never have challenged them in the first place. It was the “friendly” Muskogee chiefs — traitors who had sided with the Americans — that had poisoned the national body. As a grown man, Osceola would spare his nation the same fate. Only by exterminating the traitors could his people regain their strength.

So as Charley Emathla and Osceola stood on opposite ends of the rifle barrel in November 1835, both men could feel Tecumseh’s earthquake shifting the Florida ground under their feet.

___________

References:

Joel W. Martin, Sacred Revolt: The Muscogees’ Struggle for a New World, Beacon Press 1991.

George Stiggins, Creek Indian History: A Historical Narrative of the Genealogy, Traditions and Downfall of the Ispocoga or Creek Indian Tribe of Indians by One of the Tribe, George Stiggins (1788-1845), Birmingham Public Library Press 1989.

It is interesting to note that Tecumseh’s career was bookended with both the greatest Native American victory over U.S. military forces in history and the worst defeat (if he can be credited with an inspirational but absentee role in the Red Stick War). As a young warrior, Tecumseh fought in the Battle of the Wabash (present-day Ohio, November 4, 1791), where roughly 1,500 warriors of numerous tribes under the leadership of Little Turtle, a Miami, and Blue Jacket, a Shawnee, met an army of U.S. regulars and militia of about the same size. The American Gen. St. Clair beat a hot retreat after a four-hour engagement, leaving roughly 800 Americans dead and another 350 wounded. Native casualties were estimated at a tenth of that. No U.S. defeat at Native American hands comes close in scale. For comparison, 85 years later Gen. George A. Custer went down with 210 soldiers in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (a.k.a. the Battle of the Greasy Grass).

One authority names Charley Emathla a straight-up Red Stick. Susan A. Miller, Coacoochee’s Bones: A Seminole Saga, University Press of Kansas 2003