Before the Fire

Ch. 12: Big Sugar Crystallizes Black and Seminole Alliance

Previously, in Chapter 11, Seminoles and blacks combined to burn a New Smyrna sugarcane plantation on Christmas Day, 1835, igniting the Florida War. How did that extraordinary day start?

That morning, when Jane Sheldon heard the news from her servant girl, her heart caught in her throat. It was a shock. But not a surprise.

Nine Indians. The girl had been at the dance in the slave quarters over at the Hunter place the night before, Christmas Eve. People were having a good time by the bonfire, looking forward to some of the few days off they’d get till the following Christmas. It wasn’t unusual for Indians to show up from time to time. They were always about, just beyond the woods to the west. But these, the girl said, were painted. Everyone knew what that meant.

Certainly, Jane Sheldon needed no explanation. She ran to find her husband. The Sheldons occupied the finest home in New Smyrna. From a rise on the west bank of the Hillsboro River, they overlooked the water sweeping out toward its point of escape into the wide blue Atlantic at Mosquito Inlet.1 John Sheldon managed the big sugarcane plantation for absentee owners. The center of the operation — the sugar house and slave quarters where about 80 people lived — lay a couple miles inland.

Jane Sheldon lived at the apex of her insular society. She was a white, 22-year-old mother of two. Her little family prospered modestly. On occasion, they socialized with the small handful of white people who lived thereabout.

But her position was tenuous. And Jane would soon find out that when trouble came, help was a very long way away.

The Mosquitoes

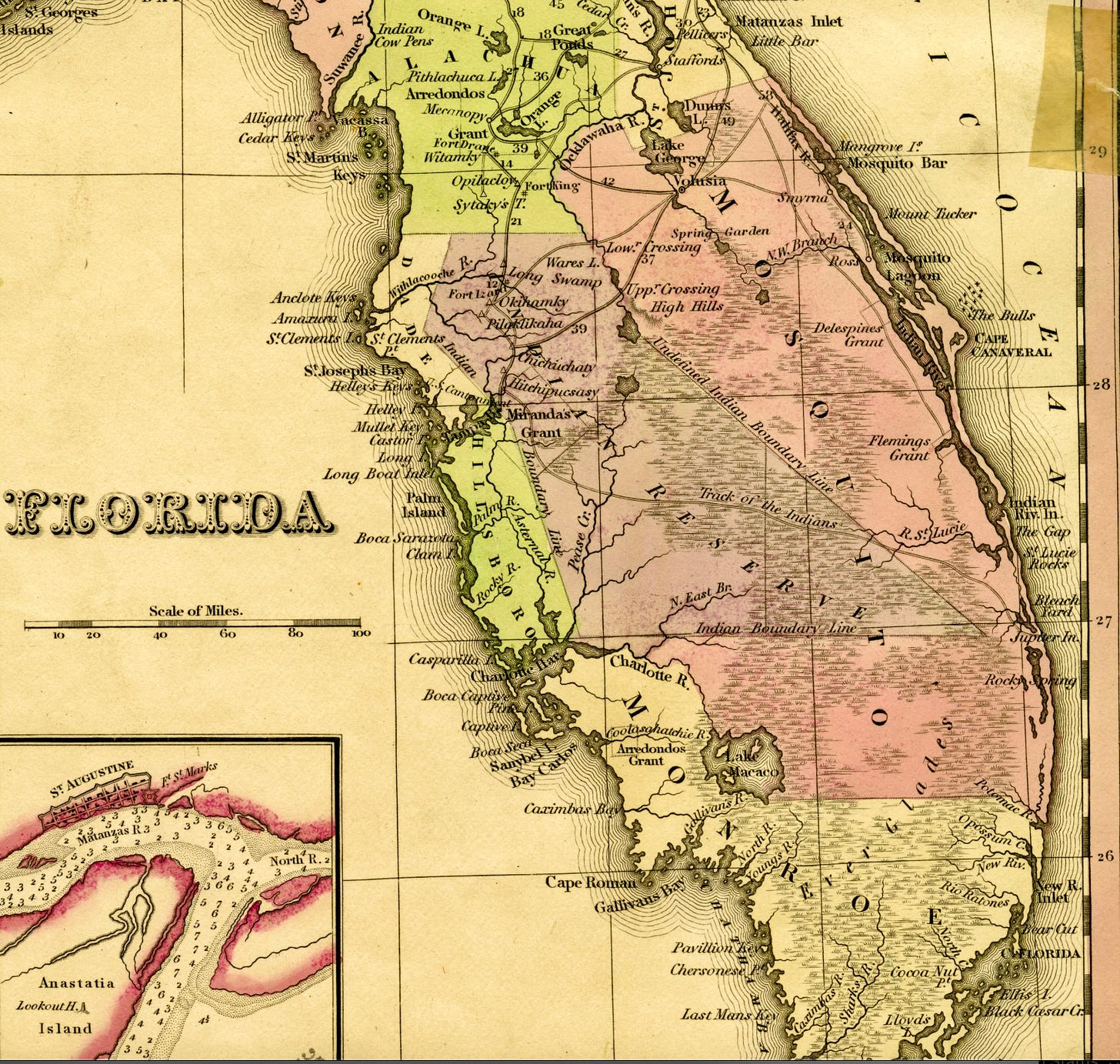

New Smyrna was a remote outpost at the southern tip of a narrow, 70-mile-long cul-de-sac. Civilization lay at the far northern end, St. Augustine, a city of 2,000 people. Between the two a string of plantations was bracketed on the west by the sandy King’s Road and on the east by the intracoastal waterway.

New Smyrna’s plantations were situated on drained swamps, an area aptly called Mosquito. Despite being home to just a couple hundred souls, the great majority of them enslaved black people, New Smyrna was the seat of Mosquito County, or, simply the Mosquitoes, a vast, unsurveyed chunk of Florida roughly 120 miles long and 60 wide at points.2

White people knew virtually nothing of the interior of central and south Florida. Maps left it mostly blank with rough guesses about the location of rivers and hammocks and the towns of indigenous and black people who lived there. In the Mosquitoes, whites and their enslaved labor force mainly stuck to the isolated plantations along the coast and a few along the St. Johns River, well inland.

The Cane — Wealth and Misery

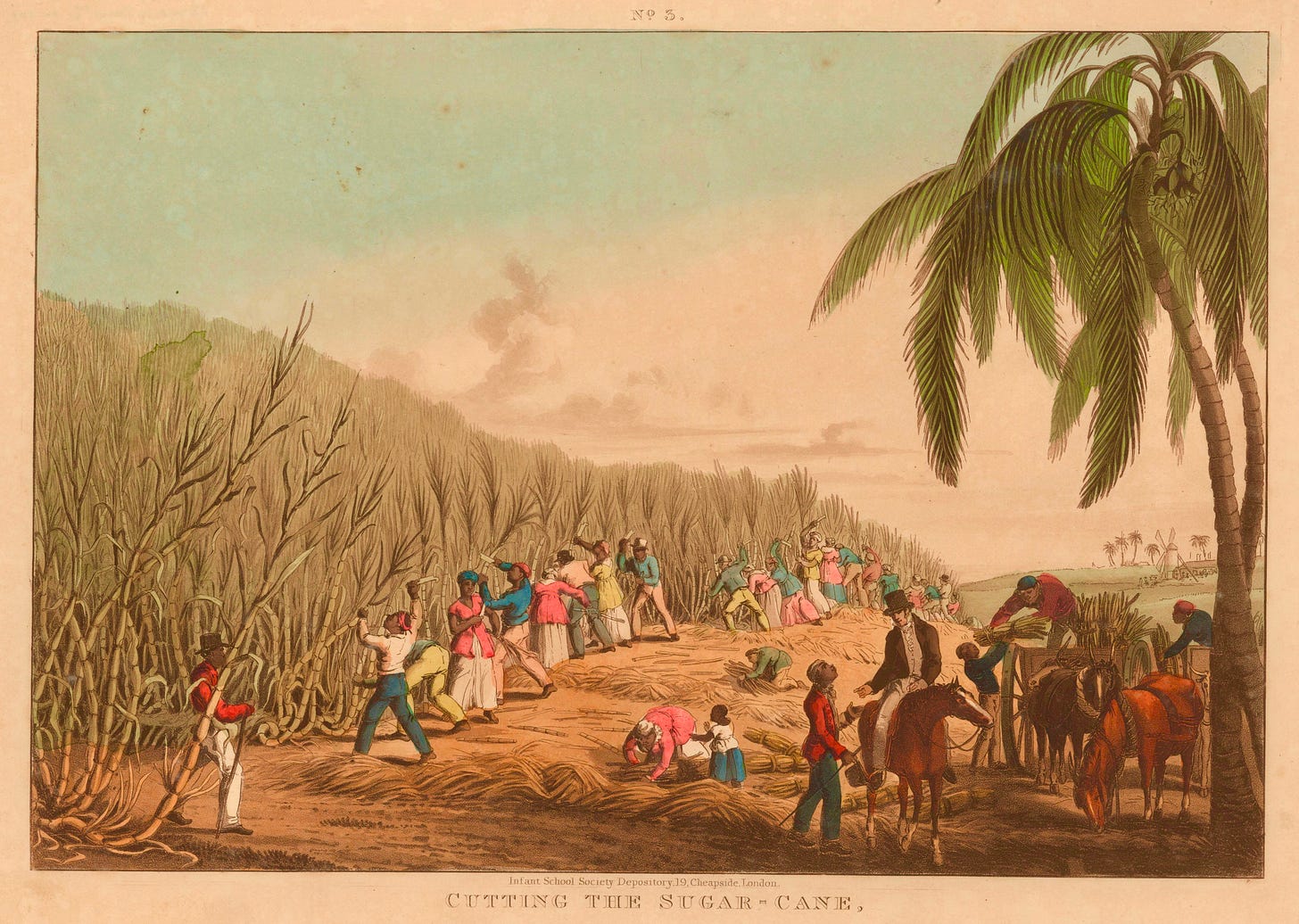

In the Americas, long before cotton, sugar was king. The sweet stuff bestowed stupefying wealth on the empires of Britain, France, Portugal and the Netherlands. In 1493, on his second expedition, Columbus first planted the exotic cane in the Caribbean islands. It thrived in the hot, wet climate of the West Indies and coastal mainland of Central and South America down through Brazil.

Sugar could be measured in dollars. But also in misery. After quickly working to death all the indigenous people they could catch, colonial powers turned to Africa for labor.

It was for sugar that Europeans created the trans-Atlantic trade in African slaves, a practice that persisted for centuries. Of the 12.5 million Africans enslaved, more than 90 percent were destined for the Caribbean and South America; just 3.5 percent came to what is now the United States.

Sugar was the difference. Africans who were brought to the U.S., which had no sugar industry to speak of, largely sustained or increased their own numbers by reproduction, which limited the trade. But the sprawling tropical sugar plantations of the Caribbean and South America were death traps, a voracious maw constantly demanding replacements for people worked into early graves.

Florida Takes a Chance

The great thumb of Florida poking down into the Caribbean was sugarcane’s northern limit. Occasional winter cold snaps made the crop dicey here. Early attempts were failures. But such was the lure of sugar wealth that by the 1820s and ‘30s, entrepreneurs with new steam technology and capital backing were willing to take the capital risk. They gambled on the chance to dip Florida’s thumb into the sugar pie.

The Cruger-dePeyster plantation in New Smyrna was Mosquito central. The two men for whom the plantation was named were New York speculators. Plunking down the nest egg of one of their wives and taking on heavy bank loans, they invested in 600 acres of mostly drained swamp, 80 slaves, and expensive, cutting-edge steam machinery for crushing and processing cane. The owners figured the enterprise would stand or fall by the vicissitudes of weather, management of labor and equipment, market prices, and the idiosyncrasies of cane cultivation.

What they hadn’t properly accounted for was the neighbors.

The Neighbors

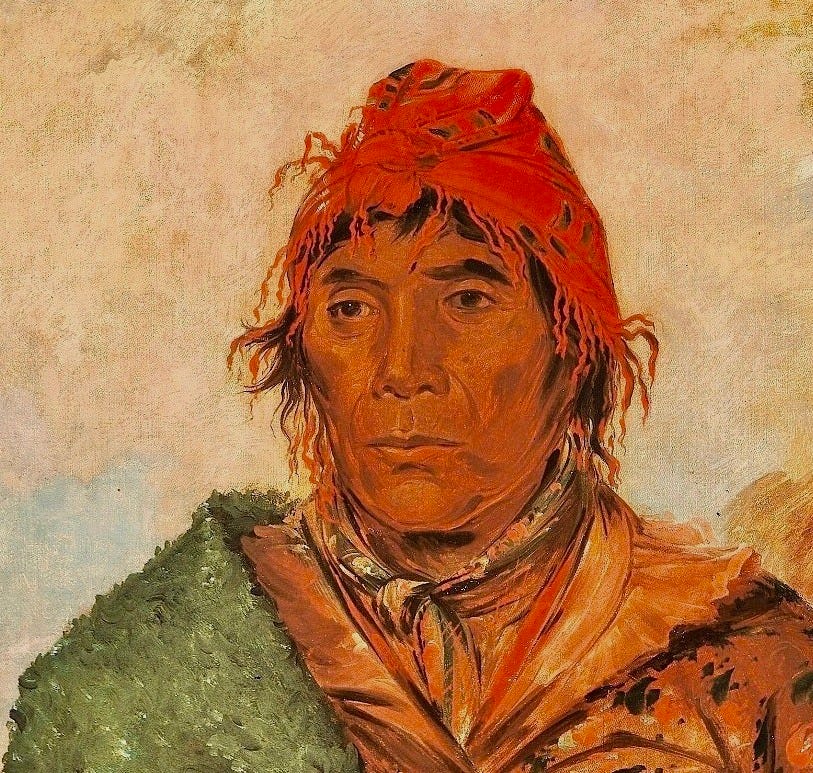

One hundred and thirty years before these New Yorkers showed up, Florida’s native people were in freefall. By 1705, warfare around Spain’s disastrous century-old mission venture in north Florida and waves of European plagues had depopulated the northern half of the peninsula. (See Ch. 2 of The Florida War.) A dozen years later, Yamassees fleeing war with the Carolina’s English colonists came south. They were joined, beginning around 1750, by Muskogee, Mikasuki, and Yuchee people from what is today Georgia. These people maintained their distinct ethnic identities and languages but, for political as well as defensive purposes, amalgamated into what was increasingly called the Seminole nation.

Beginning in the 1760s, British and then Spanish authorities tried to lure settlers to east Florida with land grants. Not small plots for yeoman farmers, but huge tracts for wealthy agriculturists who would cultivate silk, cotton, and indigo. Few were inspired to try and fewer still succeeded. (New Smyrna’s Turnbull colony, from 1768-1777, was a colossal fiasco, but that’s another story.) As the years ticked by, however, plantations built on enslaved labor crept south from St. Augustine along the coast.

Indian relations with these planters was sometimes peaceful, sometimes violent. In 1802, for instance, a Mikasuki raiding party attacked and trashed two plantations about 20 miles south of St. Augustine, near today’s Palm Coast. From one, they took ten black people. On the other they killed a white boy and hauled off his mother and four siblings. The whites were ransomed back over the next two years; the blacks were not. In the wake of this episode, plantations in the neighborhood lay abandoned for years.3

New energy came to the Mosquitoes after the United States took Florida from Spain in 1821. The Americans figured the solution to their Indian problem was to clear them away from the plantation zone and concentrate them on a reservation in central Florida. By the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823, the eastern Seminoles were to give up their lands near the coast and the St. Johns River valley.

Perhaps some did.

Among the many who did not was Emathla, an aged leader of high stature. Some reckoned him the #2 man in the Seminole nation and he was known to whites as King Philip.4 Two Yuchee head men, known as Billy and Jack, also stayed by the St. Johns with their people. However, the Yuchees, after the Moultrie Creek Treaty, were bullied off their land to make way for the Spring Garden sugar plantation owned by Orlando Rees (see map, above), complete with a great waterwheel to power its sugar mill.5 The Yuchees remained nearby, waiting for a chance to reclaim what was taken.

In the early 1830s, Emathla’s people allowed cordial relations with the new wave of American sugar planters. Commerce was more common than friction. Indians traded wild game for American goods, including sugar and its derivative rum. Individuals of one side were often well known to the other.

The intrepid Black Seminole John Caesar, Emathla’s right-hand man, was one such person. He was said to have had a wife on one of the plantations and was often seen in the Mosquitoes, bartering from St. Augustine south to New Smyrna.

Despite the detente, memories were long. Each side was keenly aware of the violence the other could bring.

Rumors of War

The remote plantations in east Florida were weeks away from the central Florida environs of Fort King and the Indian Agency. News moved at the speed one could speak it to another in person, or hand it in a letter traveling a tropical course by foot, horse, and boat. Still, by December 1835, word had reached St. Augustine that trouble with the Seminoles was looming.

Which didn’t surprise the people of that town. It jibed with the frightening rumors coming north from the Mosquitoes. Seminoles, particularly Black Seminoles, were seen on the plantations. Their presence wasn’t unusual but their message was. They were looking for recruits, selling rebellion. These men, often escaped from slavery themselves before affiliating with the Seminoles, knew all the right words.

Jane’s Last Night

Jane Sheldon owed her position to unspeakable violence perpetrated and forever threatened. It kept the enslaved at their tasks and Jane in a nice frame house.

But enslavers were always aware that violence could be turned on them. Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion was fresh in the minds of planters throughout the South. Turner’s army of the enslaved murdered 60 whites before the Virginia state militia could suppress it. In grisly response, vigilante and court-ordered executions claimed the lives of four times as many blacks, mainly bystanders.

Just four years later, whites in the Mosquitoes understood the fear of being murdered in their beds by those who would no longer live as slaves.

A similar fear troubled white settlers on disputed Indian land. On the ever-expanding American frontier, whites slept lightly with the specter of a stealthy warrior returning, tomahawk in hand, to wreak vengeance, scalp by scalp.

Unfortunately for Jane Sheldon, she was cursed with both nightmares.

So when she was told that nine war-painted Indians had a nighttime rendezvous with Africans in the slave quarters, Jane knew she’d spent her last night in the big plantation house. She probably wondered if she and her family would see out the day.

Next: White flight from the Mosquitoes.

References:

Patricia C. Griffin, “Life on the Plantations of East Florida, 1763-1848,” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 56, No. 3, Sept. 2003.

Pleasant Daniel Gold, History of Volusia County, Florida, Deland, Florida 1927.

Jane Murray Sheldon, “Seminole Attacks Near New Smyrna, 1835-1856,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. VIII, No. 4, April 1930.

U.S. Congress, House Doc. No. 225, “Negroes &c., captured from Indians in Florida, &c., Letter from the Secretary of War, Feb. 27, 1839,” 25th Cong. 3rd Sess.

Today it is the Indian River and Ponce de Leon Inlet.

The label encompassed a vast area from today’s Flagler Beach south to Ft. Lauderdale and extended landward to Orlando (not then a thing), which was on the eastern boundary of the Seminole reservation.

Friction in the early 19th century was common. In about 1803, the parents of Jane Sheldon (née Murray) were run off their newly acquired plantation in the Mosquitoes by Native Americans. The Murrays retreated to Philadelphia where Jane was born, but returned to the Jacksonville area (Mandarin) in 1829. Jane married John Sheldon there, then accompanied him to New Smyrna in October 1835, just a couple of months before the events described here.

His high stature either derived from, or was recognized by, his marriage to a sister of the primary Seminole head man, Micco-Nuppa. He was not known to be a relation of Charley Emathla. Emathla was more a title than a proper name.

Today it is DeLeon Springs State Park. Bring the kids, you can make your own pancakes on a table-side griddle in the restaurant overlooking the (re-created) waterwheel, then go dip in the springs.