Death Decree from Big Swamp

Chapter 10: Osceola and Charley Emathla finish their business

Previously, in Chapter 9, the ghosts of the Red Stick War in Muskogee country sent Charley Emathla and Osceola on distinctly different paths. Now those paths converge.

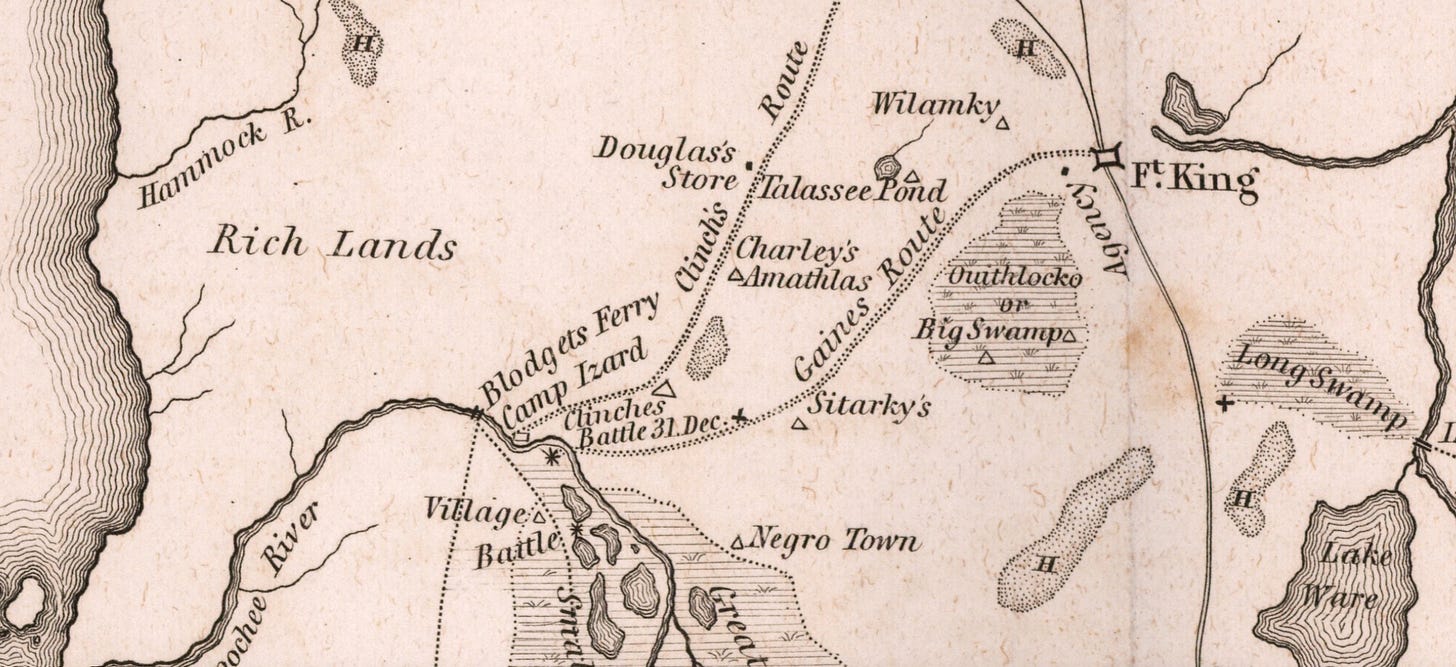

The fall of 1835 was a bad time among the Seminoles. Pressure mounted as the American date for Removal — January 1836 — closed in. A council was convened at a town in the Big Swamp, west of today’s Ocala. There, in early November, it was agreed1 that anyone collaborating with the American Removal effort would suffer death.

Like a bolt of lightning, this decree produced panic. Hundreds of Seminoles fled their towns. These were the people aligned with Removal-compliant head men Fokke Lusti Hadjo (Black Dirt), Holata Emathla and three others. After legging it over 100 miles, terrified they’d be ridden down by anti-Removal vigilantes, they fetched up at the gates of Fort Brooke on Tampa Bay. The 500 refugees asked the U.S. Army for protection from their own people.

The Big Swamp decree had served its purpose. It extruded from the nation the Removal-minded and silenced the fence-sitters. It eradicated the concept of “friendly chiefs” among the Seminoles.

Except one.

He won’t back down

Charley Emathla was literally unmoved by the threat. He remained with his people at Emathla’s Town, about 15 miles northwest of the Indian Agency (Ocala) and continued preparing for Removal in the procedure been laid out by U.S. Removal Agent Wiley Thompson.

The first step would be the cattle. Thompson’s plan — devised over months with Army officers working logistics in New York, Washington, and New Orleans — began with the Seminoles driving their cattle to Fort King to be left in his custody. A professional would appraise the value of the stock and they would be sold at public auction to white traders and incoming settlers.

In the next step, having divested themselves of everything they could not carry by hand, four or five thousand Seminoles would gather at Tampa Bay to board a U.S.-contracted fleet of steamers and schooners and sail across the Gulf to New Orleans. From there it would be flat-bottomed paddle-wheelers up the Mississippi and White Rivers to remote northern Arkansas. Disembarking 1,000 miles away in the middle of winter, the expelled Seminoles were to receive treaty-promised blankets and shawls for the cold, wet weeks-long march west under armed guard to the bottomlands of the Canadian River in what is today central Oklahoma. This would be the final destination, a demarcated reservation to be shared with the removed Muskogees. Here in the west, the Seminoles would get the value of their surrendered Florida cattle so they could buy livestock and seed to start again when their new ground thawed.

That was the grand plan anyway, and it was to begin with Charley Emathla’s cattle.

Charley hadn’t committed lightly to Removal. He understood it would be an ordeal. Having traveled to the Arkansas Territory once, he could see that some of his people wouldn’t survive it. They would be left behind in riverside or roadside graves as convenience allowed. Others would struggle and die in the cold country awaiting the first harvest from that foreign soil.

For at least three years, Charley Emathla had argued against Removal. As a chief diplomat in the two Removal treaties of 1832 and ‘33, he knew them to be the manifestation of American threats, lies, trickery and bribery. But Charley also knew that the United States, fair or foul, was bent on controlling every inch of the Southeast for its slave-labor economy and that his people were in the way.

In the end, Charley Emathla’s interest in justice was overcome by his will to survive. He came to realize that remaining in Florida would require war against the Americans. Removal, he concluded, was the less deadly option.

The Mikasukis and Alachuas of Big Swamp could threaten if they wished, but Charley Emathla — that amiable, broad-chested rancher — would not back down.

In late November, two weeks since the panicked flight of his allies to Tampa Bay, Charley was calmly continuing his Removal preparations. Surely, he was not surprised when he finally got a visit from Big Swamp.

War whoops and Judas money

Details of the visit are hazy. We have only a handful of contemporary reports, and these are second- or third-hand.

The most dramatic telling comes from Thomas McKenney and James Hall. They tell of a posse of 400 warriors (a wild exaggeration) surrounding Charley’s house. Two men were prominent in this party: one was Osceola and the other was Abraham, the man who had escaped slavery to become the counselor and interpreter for the nation’s primary head man. They called Charley out and demanded he abandon his Removal plans. Charley emerged and told them to go pound sand, that Removal was the only hope for his people.

At this, Osceola leveled his rifle on Charley. But Abraham grabbed his arm, defusing him. Abraham was in no hurry to shed blood. He called on the posse to retreat awhile and think things over. Executing a top Seminole leader would be a Rubicon move; there must be some way to convince Charley. They withdrew.

In the meantime, Charley Emathla went to the Agency at Fort King, perhaps to arrange the disposition of his cattle. He told his friends there they might not see him again because men had been assigned to kill him. He then turned to face his fate.

“He left the agency accompanied by his two daughters, and preceded by a negro on horseback, and had travelled homewards a few miles, when Asseola, with twelve other Indians, rose from an ambush, gave the war whoop, and fired upon him.”

— McKenny and Hall at p. 381

But Charley wasn’t finished in this rendition. He stood in his stirrups, sang out his own war whoop and charged his assassins. Once in amongst them, he “fell like a hero, perforated by eleven bullets. Thus died the chief of the Witamky band, a gallant, high-minded leader, and a man of sterling integrity….”

Another report, from John T. Sprague, differs. In this one, there is no preliminary meeting or discussion. Osceola and his party lay in ambush for Charley who was returning to his village after selling his cattle at Fort King.

Charley fell in the first fusillade, “prostrate upon his face, and covering his face with his hands, received the death blows of his enemies without uttering a word.”

— Sprague at p. 88

But buried in the footnote is the iconic detail that may forever frame the confrontation between Charley Emathla and Osceola:

“[Charley Emathla] had in his handkerchief a sum of gold and silver received from the agent for his cattle. This Oseola said was made of the red man's blood, and forbid any one touching it, but with his own hands threw it in every direction.”

This was the end of Charley Emathla. The dead man was left on the sandy soil, his bullet-ridden body to be picked clean by wolves and vultures. No one dared touch him until long afterward when an Army detail allegedly buried those bones they could find.

The rising in the stirrups, the bloody gold and silver, even the cattle sale may be true or invented. But all accounts agree: Osceola led the death squad against his former compatriot.

Charley’s death draws the line

If the cold death decree from Big Swamp had put everyone on notice, Osceola’s hot lead finally exploded the notion of a non-violent Removal. In a November 30 letter to his superiors, Wiley Thompson put it this way:

“On the 26th inst. Charley Emartly, the most intelligent, active and enterprising chief in this part of the nation, friendly to removal, was murdered by those opposed to the removal: this murder was effected through the agency of a sub-chief; [Osceola] who professed to be and was considered friendly. The consequences resulting from this murder, leaves no doubt that actual force must be resorted to for the purpose of effecting the removal….”

Fort King was briefly paralyzed. The handful of Native people at the fort refused to venture beyond its gates. Word filtered in that Charley Emathla’s Town had been deserted, his people likely joining the anti-Removal party on tenuous terms. There were rumors that the Seminoles, expecting war, had retired to defensible camps in the vast swampy Cove of the Withlacoochee River.

The bushwhacking of Charley Emathla had not been an act of war. It was an internal matter. Still, it had drawn a bright battle line against the United States. For weeks an uneasy hush settled across central Florida as the two sides crouched and honed their war plans.

Wiley Thompson, the tireless Agent of America’s Removal program, saw his well-crafted plans go up in smoke. But Wiley still had a crucial part to play in this story. Osceola would make sure of it.

References:

Thomas McKenney and James Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America: with biographical sketches and anecdotes of the principal chiefs, Vol. II, Philadelphia 1872.

John T. Sprague, The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War, D. Appleton & Co. 1848.

Letter from Gen. Wiley Thompson at Seminole Agency to Brig. Gen. George Gibson, November 30, 1835 in Document No. 271, House of Representatives, 24th Cong., 1st Sess., “A supplemental report respecting the causes of the Seminole hostilities, and the measures taken to suppress them,” June 3, 1836, p. 241.

Woodburne Potter, The War in Florida: being an exposition of its causes, and an accurate history of the campaigns of Generals Clinch, Gaines and Scott, Baltimore 1836, pp. 94-5.

Commentators have described this as the law of the Seminole nation. But that’s not how it worked. The Seminoles, like most Southeastern peoples, were highly democratic, but not a democracy. There was no concept of majority rule. People were only bound to follow policies adopted by consensus. At the time of the Big Swamp meeting, up to one-third of the nation was resigned to or leaning toward Removal. These people could not have participated in a consensus-derived law promising themselves death. So the decree was a naked threat adopted by the majority to coerce the minority.