Osceola Agrees to Removal

Chapter 6: Jailhouse Conversion - Will It Hold?

In the previous post: Osceola, a dynamic enemy of America’s Removal project, appealed for release from jail. The Agent considered appropriate terms.

Jail undid Osceola. After just a couple of days shackled in a dark room he was a wreck. White soldiers jailed for theft or drunkenness took their punishment in stride. But incarceration had a dire effect on Osceola.

So much so that he submitted completely. The most ardent opponent of Indian Removal suddenly offered to switch sides. In exchange for his release, he agreed to mark the paper acknowledging the Removal treaties. It was a stunning reversal. For months, Osceola had been at the forefront of resistance to the treaties, always goading his superiors to stand firm against them and threatening those Seminoles who considered emigration.

But this reversal wasn’t enough for the Superintendent for Removal of the Florida Indians, Wiley Thompson. Wiley, who had Osceola thrown in the can on one count of rudeness, wanted more.1

“I informed him that, without satisfactory security that he would behave better and prove faithful in the future, he must remain in confinement. He sent for some of the friendly chiefs and begged them to intercede for him; they did so.”

It’s a fair surmise that Wiley told Osceola he’d rot in jail until he declared, in front of his countrymen, that he had switched from the ‘remain’ to the ‘exit’ side, that he would leave Florida.

At this point, Osceola probably would have done anything to get out of jail. We see this not just from the fact of his abject conversion; there’s a clue in Wiley’s correspondence. Less than a month after these events, Wiley advised a Florida militia captain on how to handle Seminoles who had crossed outside of the reservation boundary without permission.

“[A]nd I think it will have a good effect on them,” Wiley wrote to the captain, “to lodge them in jail. The idea of a jail carries terror to the Indian’s mind.”2

Maybe Wiley had jailed Osceola intending to terrorize him, or maybe Wiley just learned of jail’s terrorizing effect by watching Osceola crater. Either way, Wiley had no compunction about holding Osceola to extort concessions from him. If terror gripped the Seminole war chief’s mind, as Wiley’s words imply, Osceola’s jailhouse conversion becomes more understandable.

Charley Emathla bails out Osceola

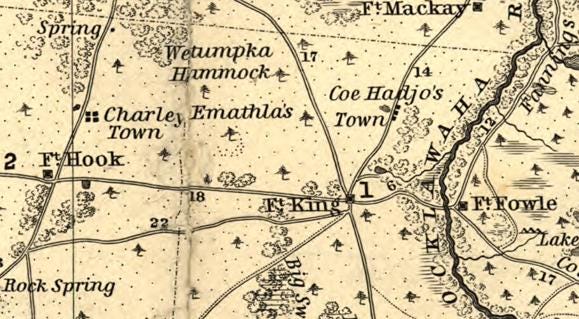

Charley Emathla was among the “friendly chiefs” summoned to Fort King’s jail to vouch for Osceola. He was probably as surprised as anyone at Osceola’s compliance. Charley was the head man of an eponymous town about 15 miles northwest of the fort. He was well respected in the nation, an important figure in council.

Wiley called Charley “friendly” not because of his disposition — though Charley may well have been cheerful — but because he was on board with American policy. There were no enthusiastic Native cheerleaders for Removal. Exile was universally dreaded. But American pressure, military threats, and wretched, near-starving conditions in some Seminole towns led some to see emigration as the only hope for survival.

Charley Emathla had been one of the seven Seminole head men who had traveled more than 1,000 miles with the Americans to scout the Arkansas territory in the winter of 1832-33. Although Charley marked the so-called “Treaty of Fort Gibson” in March 1833, approving that distant country as a liveable place, on his return to Florida that spring and through the winter of 1835, Charley had opposed Removal as did all other head men in the central Florida reservation.

But by May of 1835, Charley had been worn down. He, along with two other principal chiefs — Holata Emathla and Fakki-Lusti-Hadjo (a.k.a. Black Dirt) — had agreed to America’s removal demand so long as they could remain in their homes through the fall harvest and leave in early 1836. These men sat on the minority side of a sharp divide among the Seminoles. The majority, including Micco-Nuppa and most all of the top leadership, had determined to remain at whatever cost.

It wasn’t a simple stay-or-go choice. Many saw Charley, Black Dirt and other emigration men as traitors, collaborators. They weakened the fabric of the nation. These “friendly” chiefs suffered abuse and death threats. Up until the day Wiley had thrown him in jail, Osceola was a leader of these militants. As a boy, he had seen his Muskogee nation broken by the split between “friendly” Creeks and the Red Stick faction that opposed assimilation. He had been determined never to see such division again.

But jail turned Osceola, and now he summoned Charley Emathla and other friendly chiefs to come bail him out.

The men came and sat with shackled Osceola. It must have been an extraordinary humiliation. After some time, they asked Wiley Thompson to release him.

Wiley goes big, Osceola goes bigger

Wiley told Osceola he could walk on the promise he’d return in five days to mark the treaty recognition document in public council with the friendly chiefs. It was an odd demand. Perhaps Wiley felt it would appear less extortionate to give him five days. But conditioning freedom on political compliance is blackmail however you slice it.

Now, Osceola could have walked out of Fort King and never looked back. That would have been perfectly reasonable. Morally, he owed Wiley nothing. Or maybe, recognizing a debt to Charley Emathla and others for their efforts, Osceola could have returned alone and grudgingly marked the document.

But in this bizarre tango, Osceola went all in. After five days, Osceola returned to Fort King leading “79 of his people, men, women, and children.” Osceola told Wiley he’d have brought more but they were out hunting. Then, in front of these and the assembled head men, Osceola took up the feathered quill, dipped it into the inkpot and scratched his X on Wiley’s paper.

It was an impressive show — proud Osceola humbling himself, acknowledging his errant ways.

Wiley might have guessed that a promise pried under duress was no promise at all. And he surely knew Osceola well enough to know the stakes of the game. According to our Pvt. Bemrose, Wiley had been warned by the fort’s commander, Lt. Col. Alexander Fanning (who later named a fort for our Lt. William Maitland), that “he expected Osceola to become his most determined enemy.”

But Wiley Thompson saw only success. He was overjoyed! This was the result he’d so long sought. To think, after all that wasted breath in those dreadful conferences, all he really had to do was throw a young hothead in jail. Osceola’s conversion fit right into Wiley’s worldview — spare the rod, spoil the child.

Boasted Wiley to his superiors, “I have now no doubt of his sincerity, and as little, that the greatest difficulty is surmounted.”

In fact, so moved was the miserly Agent that he presented Osceola with a special gift. As the crowd looked on, Wiley handed the Tallassee tustenuggee a rifle. For Wiley, the stick of imprisonment had worked well, but he wanted all to see that carrots were also on offer for those who submit.

Osceola accepted the weapon, heavy in his hands. It was a beauty. An expensive, custom number, no standard-issue musket nonsense. Osceola smiled as he balanced the well-weighted rifle. He nodded to the Agent, holding his gaze for a moment, and then turned to Charley Emathla, and nodded to him, too.

This moment, this gift, would spell out the fate of all three men.

_______________

Sources:

Randal J. Agostini, An Englishman in the Seminole War: A Memoir Based Upon the Letters of John Bemrose, Florida Historical Society Press 2021.

Letter from Gen. Wiley Thompson at Seminole Agency to Brig. Gen. George Gibson, June 3, 1835 in Document No. 271, House of Representatives, 24th Cong., 1st Sess., “A supplemental report respecting the causes of the Seminole hostilities, and the measures taken to suppress them,” June 3, 1836, p. 198.

Wiley Thompson is the source for this account of Osceola’s imprisonment and release. See sources, listed. There are several other accounts which differ in important details. For instance, Sprague says Osceola was held 6 days before appealing for release while Thompson said the request came just a day after he was confined. See John T. Sprague, The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War, New York 1848., p. 86. The reasons given for the confinement also vary widely, as noted in previous post. But since Wiley Thompson was one of just two or perhaps three (if an interpreter was present) eyewitnesses, we’ll stick with Wiley’s account and a course-ground grain of salt. Wiley, however, does not mention giving Osceola a rifle. That comes from other accounts. See, for instance, Mark F. Boyd, “Asi-Yaholo or Osceola,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXXIII, Nos. 3 & 4, January-April 1955 at 275.

Wiley Thompson to Capt. S.V. Walker, June 23, 1835. Doc. No. 271 at p. 238.