Osceola Makes his Closing Argument

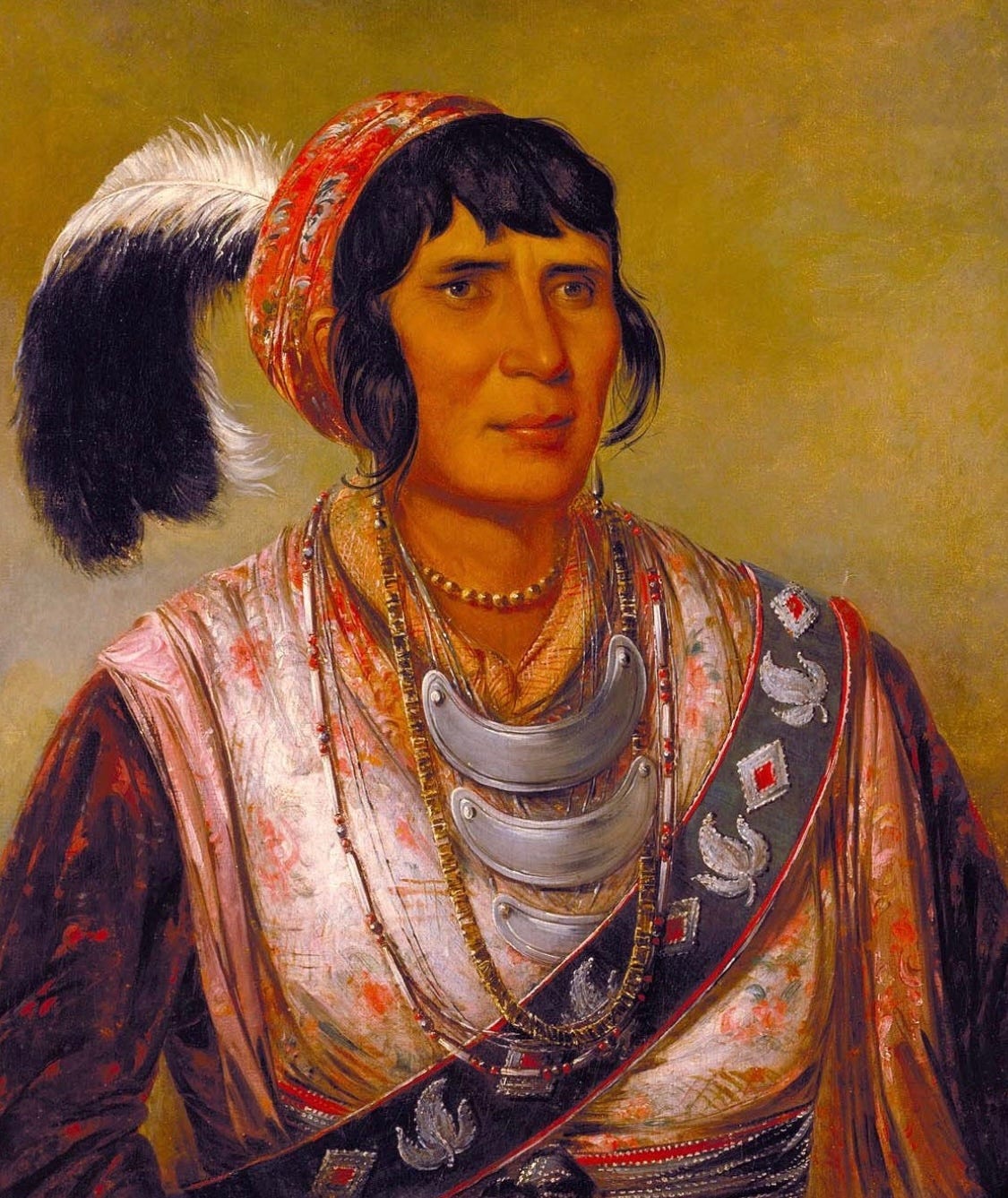

Chapter 10.5: George Catlin captures the war chief's image and his story

Previously, in Chapter 10, Osceola executed fellow Seminole Charley Emathla. Americans, of course, reviled him for this. What was the Seminole side?

Osceola was in particularly bad shape, probably suffering from malaria, among other things. “[H]e is grieving with a broken spirit,” Catlin wrote, “and ready to die….”

So Charley Emathla was the tragic hero and Osceola the treacherous villain. The victors’ history tells us so. Every contemporary report comes from a white man in the service of the U.S. government. Charley-as-martyr served their purposes.

But what was the Seminole side of the story?

They didn’t leave durable records. Still, there is a possible second-hand source.

It comes from the artist George Catlin, famed for painting the portraits of hundreds of Native Americans across the western U.S. in the 1830s, back when it was mostly all Indian country. Journeying from the Mississippi west to the Rockies, from Texas north to Montana, Catlin visited some 50 tribes, capturing portraits and ’slice of life’ scenes of war dances, ball games, and buffalo hunts. For years, he displayed his work in New York, London and Paris. Perhaps more than anyone else, Catlin cemented in the American and European mind’s eye the image of Native Americans.

Catlin left a written record, too, publishing several books about his travels. In these, we find a very different picture of Charley Emathla.

[Spoiler Alert: we’re jumping ahead two years to 1838, discussing the fate of Osceola and the course of the Florida War.]

In January 1838, Catlin had finished his painting tours of the American West and was promoting his work in New York when he got interesting news. The celebrated Seminole war chief Osceola and other top leaders were prisoners of war at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island in South Carolina. Along with 240 other men, women and children, they awaited deportation to Oklahoma. Catlin, equal parts entrepreneur and artist, collected his tools and hustled south. At the time, the ongoing Seminoles’ war for independence was a staple of national headlines. These prisoners would make fantastic — not to mention lucrative — additions to Catlin’s oeuvre.

At Fort Moultrie, Catlin found the Seminole captives haggard and resigned to fate. For two years, they had been fighting and fleeing American forces through forests and swamps, continually on the run. Although the war still raged back in Florida, it was over for these people. Osceola was in particularly bad shape, probably suffering from malaria, among other things. “[H]e is grieving with a broken spirit,” Catlin wrote, “and ready to die….”1

Catlin was given the run of the place, including officers’ quarters for his stay. The Seminoles, too, moved freely about the grounds (despite being lightly armed). Catlin reports that “on every evening, after painting all day at their portraits, I have had Os-ce-o-la, Mick-e-no-pa, Cloud, Co-a-had-jo, King Phillip, and others in my room, until a late hour at night, where they have taken great pains to give me an account of the war, and the mode in which they were captured, of which they complain bitterly.”2

Catlin gives a wildly unorthodox account of the war’s origin and progress, bearing little relation to other American versions. One might expect it to be a complex tale with lots of characters. But Catlin’s is concise and focuses exclusively on Osceola and the long-dead Charley Emathla. Did Catlin get it from Osceola in one of the late night sessions? Perhaps we hearing from Osceola, after all.

It is worth quoting Catlin at length:

“With the Seminolees in Florida, the process of moving them was a very disastrous one on both sides. The draft of a treaty for the chiefs to sign, by which they were to agree to exchange their lands for a country west of the Mississippi, was laid before the chiefs in council, who all refused to sign it, assigning as their reason that their parents and their children were buried around them, and that the country was their own, given to them by the Great Spirit, and that they would therefore never remove from it.

“The treaty was several times urged upon them without success; but it being announced to the eleven subordinate chiefs one day, that Charley Omatla [sic], the head chief, had agreed to sign the treaty the next day — which they could not believe — they all assembled, and went to the Government agent's office, where it was to be done, with their rifles in their hands, to see if their chief was going to do so treacherous an act. With these chiefs came Osceola, whose name you all have probably heard; he was not a chief, but a desperate warrior, and of great influence in the tribe.

“The treaty was spread upon the table, and Charley Omatla, according to his promise, supposing the other chiefs would follow him, stepped forward, and leaning over the table, made his signature to the treaty, and as he was rising up from the table, the bullet from Osceola's rifle, and then six others from the chiefs, were through his body before it was to the ground, where he fell a corpse.”3

Catlin’s tale not only elevates Charley Emathla to primary chief, it cuts him down right at the treaty table. But there is more.

“The treaty was ratified; and though it was subsequently proved on the floor of the Senate that the chief Charley Omatla had been bribed with 7000 dollars, still the tribe was removed by force under the treaty….”

There is no telling where Catlin got that. Perhaps Osceola claimed Charley was bribed, but it is doubtful the war chief kept up with the doings on the floor of the U.S. Senate. To my knowledge, this claim that Charley was bribed is unique, appearing in no other source (not to mention that $7,000 would have been an eye-watering sum at the time).

Catlin’s description of the Florida War, with Charley executed, continues with a singular focus on Osceola.

“Osceola fled into the wilderness, the chiefs following him as their leader—for, by the custom of all American Indian tribes, he who kills the chief in his own tribe is, de facto, chief, as long as they allow him to live: if his act is approved, no one can object to his lead; and if it is not approved, he is at once destroyed….

“The gallant Osceola, at the head of his Spartan band of warriors, retiring before some 10,000 disciplined troops, kept them at bay for six years, bravely disputing every foot of ground. He was at last captured, however (or rather kidnapped)….”4

Catlin’s account is an outlier, a wild card. No piece of it aligns with the verifiable facts or with other American sources. Charley was not the principal chief. He did not mark either treaty first. He was not alone in marking them. (In fact, Osceola put his own mark to at least two Removal documents.) No one was assaulted, much less slain at a treaty table. Osceola did not become the “de facto” primary chief. Osceola was in the field of battle less than two years, not six. The single alignment of Catlin’s tale with the facts was that it was Osceola who shot Charley.

So Charley Emathla is the treacherous villain and Osceola the tragic hero. Maybe Catlin was pumping up Osceola’s status to sell more books or to juice the value of the portraits and sketches he had made of the man. Osceola was already a fixation of the American press. Not for his hand in starting the war, but because of the public outrage that had boiled over at the manner of his capture: American troops took him and 80 of his warriors under a white flag of truce. Newspapers had a field day raining shame on the U.S. Army; its officer corps convulsed with embarrassment. Maybe Catlin was trying to leverage that martyr image.

But the focus on Charley Emathla is odd. The war had a three-year build-up involving a colorful cast of players on both sides. The war itself had been raging for over two years when Catlin visited the Seminoles. Hundreds had died and were dying. Yet Catlin’s whole story boiled down to why, long ago, Charley Emathla had so richly deserved assassination.

This smells less like art promotion than self-justification.

As Osceola neared death (he would die within a week of Catlin’s departure), he may have been haunted by Charley Emathla’s ghost. Osceola had executed a revered head man, perhaps even a fellow Red Stick Muskogee, a man who had helped spring him from jail. A man who, given all the misery and death Osceola and the other captives were leaving behind in Florida, might have been right all along.

In Catlin’s spacious quarters, as a dying prisoner in January 1838, the war chief Osceola still had a story to tell. Maybe one that he hoped would justify murder.

References:

George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians: Written during eight years' travel amongst the wildest tribes of Indians in North America, in 1832, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 and 39, Vol. II, London 1841.

George Catlin, Life Among the Indians, London 187-?.

Catlin, Letters and Notes, at 220.

Id.

Catlin, Life, at 202-203.

Id. at 204.

I had no idea Catlin's account differed so radically from other accounts. And I'm persuaded by your explanation of why. Fascinating!