Pack Up the Plantation

Ch. 13: John Caesar, Black Seminole, Has Business in New Smyrna

Previously, in Chapter 12, Seminoles in war paint appeared on a sugarcane plantation in the Mosquitoes. They were ready for change.

It was Christmas morning and John Caesar had some livestock to sell.

Or so he said.

The target of John Caesar’s pitch, Mr. Hunter, wasn’t in a buying mood. In fact, he wasn’t in a door-opening mood, either.

John Caesar stood in the yard. He was a seasoned pro. No longer a young man, he had gained a lifetime of approaches. But try as he might, he could not get Mr. Hunter to come out to have a look at the animals.

Mr. Hunter stayed firmly within his house. As if his life depended on it.

Hunter ran a sugarcane plantation along the tidal river in New Smyrna, about a mile north of the big house where Jane and John Sheldon lived. It was at the slave quarters of Hunter’s place where, the night before, the Sheldons’ servant girl had seen the war-painted Indians. Hunter may have heard about their appearance, too. In any case, there was zero chance Hunter was coming out of the safety of his four walls to converse that morning with the Black Seminole, John Caesar.

A man of distinction

John Caesar was counselor, and possibly vassal, to the ranking regional head man, a Seminole, probably Mikasuki, known to the whites as Emathla or King Philip. John Caesar gallops through the records of this period, but his background is lost to us. Still, from his Anglo first name and the Roman one after it (a quirk of enslavers was to fasten epic Greek or Roman names onto people they enslaved: Pompey, Scipio, etc.), it is a fair surmise that he had escaped bondage or was bought out from it. John Caesar occupied a powerful position. His proximity to American slavery gave him two things valuable to the Seminoles: he understood how whites and blacks thought and behaved, and he spoke their language.

John Caesar was therefore Emathla’s man of business when dealing with whites. That is not to say John Caesar wasn’t on his own errand, too, when he tried to coax Mr. Hunter from his house. John Caesar and Emathla were done with the plantations. Emathla wanted the land free of them. John Caesar wanted freedom for the people on them. Both men were ready for a new era in the Mosquitoes.

Mr. Hunter was keenly aware such an era would have no room for him. If he’d been so foolish as to accept John Caesar’s invitation that Christmas morning, he might have been murdered as he stepped off his front porch.

In time, John Caesar gave up, moved on. When Hunter figured the coast was clear, he hustled down to the Sheldons’ place on the river. Time is short, he told them. An attack is imminent. They must load up the boats with all the property they could carry and get out of New Smyrna.

The Slow Burn

The appearance of painted Seminoles and John Caesar’s failed livestock sale were not the first indications of trouble in the Mosquitoes. Months before Christmas 1835, rumors of unrest roiled the eastern plantations. White interactions with Seminoles had been unpleasant.

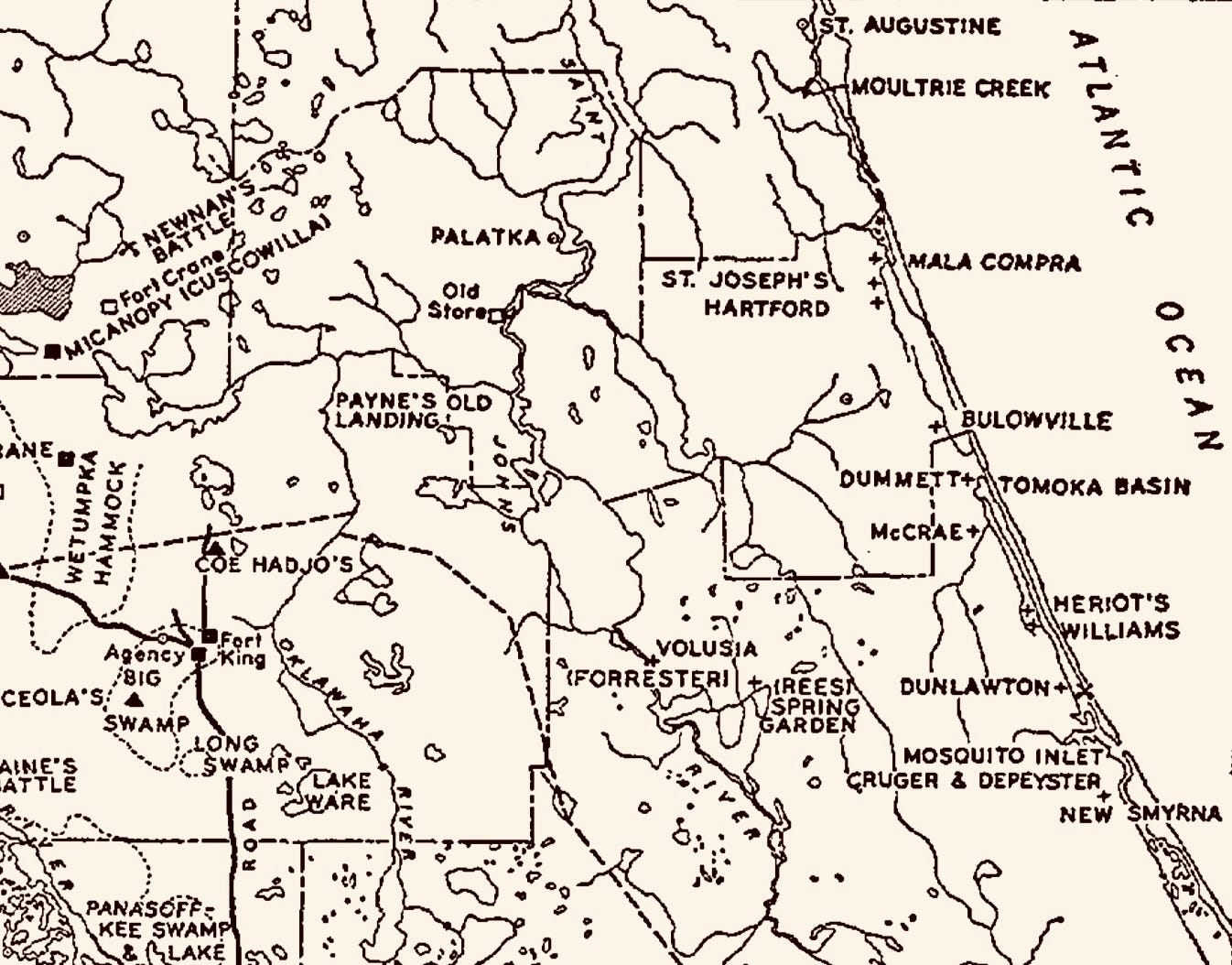

To the west in central Florida, the fall was punctuated by isolated episodes of violence. It was said that Seminole warriors were sending their women and children into remote camps. Whites near the reservation border began leaving their homes and crowding into fortified zones at Fort Crum and Newnansville (near today’s Gainesville). With the murder of Charley Emathla in late November near Fort King (today’s Ocala), it was felt that war was certain.

At the same time back in the east, Joseph Hernandez, a St. Augustine lawyer and sugar planter, was getting edgy. Hernandez was also brigadier general of the volunteer militia of east Florida. He was responsible not just for defending the city, but every sugar operation all the way down to New Smyrna in the Mosquitoes, some 70 miles away.

Before John Caesar showed up on Hunter’s plantation, he had come to the attention of Gen. Hernandez. According to an acquaintance of Hernandez’s:

“It was known that, just before the war broke out, a very intelligent and influential Indian negro, named Caesar, had visited the plantations generally on the St. John’s River, and it was supposed that he had been commissioned by the chiefs to hold out inducements to the negroes to join them.”

— Thomas Douglas, p. 121

Another contemporary account was more direct about the threat.

“[I]ntelligence reached Gen. Hernandez at St. Augustine, that a large body of Indians belonging to the tribe of Philip, and headed by an Indian negro slave, by the name of John Caesar, had concentrated themselves near the plantation of David Dunham, Esq., at Mosquito — that they evinced a disposition to be hostile, and had been tampering with the negroes, particularly those on the plantations of Messrs. Cruger and Depeyster.”

— M.M. Cohen, pp. 86-87

The militia is mobilized

In mid-December 1835, Hernandez dispatched militia units to protect plantations in the areas of Matanzas, Tomoka, and Mosquito. The idea was move south to New Smyrna and then turn west to the St. John’s, flushing out Seminoles along the way.

But Hernandez’s militia forces were few and east Florida was a rough and sparsely populated place. The expedition got as far south as Darley’s plantation (just north of today’s Ormond Beach) then pulled back and headquartered at the Bulow plantation, more than 30 miles short of New Smyrna.

The slaveholders of the Mosquitoes had put themselves in a precarious position. If John Caesar was indeed poised at the head of a Seminole war party, and if a good number of enslaved people were disposed to join him, the few whites there had no chance.

It was math. Eighty people were enslaved on the Cruger-dePeyster plantation. There were similar but probably smaller numbers on the Hunter and Dunham farms meaning New Smyrna was home to maybe 150-180 black people. But there were no more than a dozen white people around. There were the Sheldons: Jane, her mother, and husband John. Mr. Hunter and Mr. Dunham were two more and perhaps each had a white overseer on his plantation. Old Col. Dummett resided across the river from New Smyrna and his adult son was somewhere in the area.

For the white community of New Smyrna, trouble was coming. But help wasn’t.

To the boats

After John Caesar’s visit, Mr. Hunter and the Sheldons spent Christmas Day preparing their escape. The boats they used were lighters, oar-powered cargo vessels that shuttled goods between the riverside wharf and ships anchored in deeper water. But it wasn’t just household goods they loaded.

Their understanding of ‘property’ was larger than that. It included the people enslaved on the plantations. On the ledgers of the Cruger-dePeyster sugar operation, these were the most valuable assets. The records do not indicate how many black people boarded the lighters — was it 6 or 36? — but some number did.

By sunset, they had shoved off and were crossing the river. Mr. Hunter and the Sheldons hoped to find temporary safety at old Col. Dummett’s house on the far side.1

We will never know, but perhaps John Caesar stood on the west bank of the Hillsboro River2 watching as the lighters grew smaller in the distance. If he did, maybe he felt that it was just as well his livestock sale had fallen through that morning. Without selling a cow, and more importantly, without firing a shot, John Caesar and the Seminoles, and the specter of slave insurrection, had wrung New Smyrna free of white people. There would be no more masters on these sugar plantations.

For John Caesar, that was a good start.

References:

Mark F. Boyd, “The Seminole War: Its Background and Onset,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 1 (July 1951).

M.M. Cohen, Notices of Florida and the Campaigns, B.B. Hussey, New York, 1836.

Autobiography of Thomas Douglas, Late Judge of the Supreme Court of Florida, Calkins & Stiles, New York, 1856.

Ryan P. Horvatter, The Florida Volunteers: Territorial Militia in the Opening of the Second Seminole War, Master’s Thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2021.

Kenneth Wiggins Porter, “John Caesar: Seminole Negro Partisan,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Apr. 1946).

Jane Murray Sheldon, “Seminole Attacks Near New Smyrna, 1835-1856,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. VIII, No. 4 (Apr. 1930).

Dummett’s house was in the area just south Flagler Avenue where the North Causeway touches down on the island side of New Smyrna. His grandson’s grave is still evident there on Canova Drive.

It is now called the Indian River. The Sheldon house sat on the current site of Old Fort Park in New Smyrna Beach, where the North Causeway touches down on the mainland. The NSB History Museum is on the next block or you can get some grub at the River Deck Tiki Bar & Restaurant across the street while watching the dolphins swim by.

I have long been amazed by how slaveholders were so willing to be vastly outnumbered by the people they enslaved. I am thinking of the ratio of enslavers to enslaved in places like South Carolina. Did they really ever sleep easy at night, I wonder?

This is a nice read.

I know this isn't the main point, but I love thinking about how Roman history lurks in unexpected corners.

Using names like Pompey or Scipio carried fragments of Rome into a context half a world and centuries away. I wonder if a figure like John Caesar had a greater grasp of ancient history than someone in an equivalent social position today would.