Removal Splits Seminoles: Charley Emathla's No-Win Choice

Chapter 8: Osceola Becomes an Unlikely Ally

Previously, in Chapter 6, Wiley Thompson was finally getting results. The U.S. Indian Agent had conditioned Osceola’s release on his promise to submit to Removal. Osceola, from a cell at Fort King, summoned Charley Emathla and other Seminole head men to witness the pledge and serve as its guarantors. This was the price of Osceola’s freedom in June of 1835. But Wiley and Charley would find the cost much higher.

For Wiley Thompson, it was problem solved. Osceola, the most vocal obstacle to Removal in the Seminole nation, had been tamed. A few days in lock-up was all it took to get Osceola to agree to mark his “X” on what was essentially his own deportation order.

It is harder to imagine what Charley Emathla felt as he watched Osceola humble himself at Fort King in June 1835. Charley, too, had recently agreed to submit to the Americans’ Removal program. But Charley got there through years of reflection, not sudden compulsion. Was Charley revulsed at Osceola’s weakness? Maybe he was relieved to have Osceola on his side, by whatever means. Osceola’s smarts and ambition were not in doubt. It was certainly better to keep such a man as a friend than an enemy. But did he trust that Osceola, mercurial and a generation younger than Charley, would stick to this pledge of pacifism?

Osceola had made a great show of sincerity, trooping in dozens of his townspeople to stand witness to his conversion alongside Charley and several other pro-Removal head men. It was almost too much.

Charley Emathla might have wondered, standing there in the punishing sun as Osceola was delivered into his fold, if he had just been handed a rattlesnake.

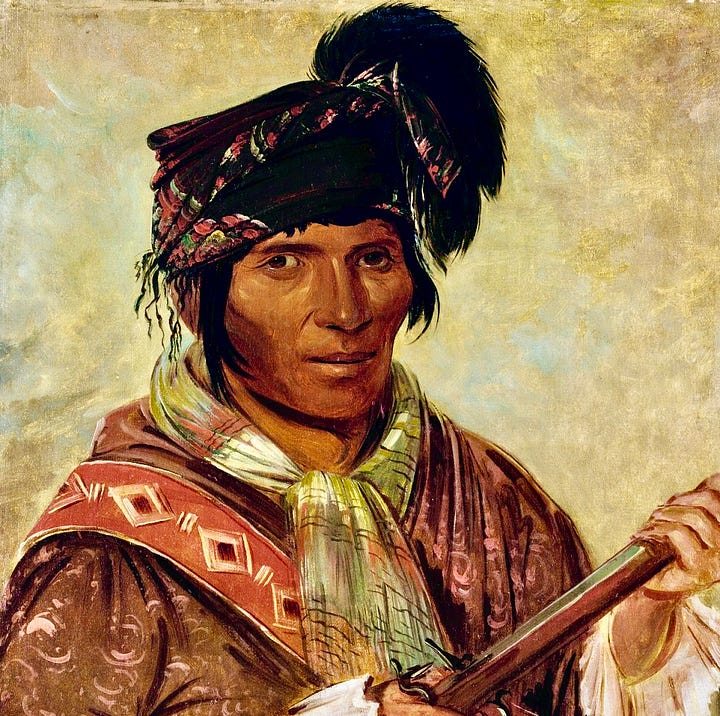

By all accounts Charley Emathla was a pivotal figure in the run-up to the Florida War. He was one of the most revered leaders of the coalescing Seminole nation. He strides through the historical record for three years, 1832-1835, a major player at every major point. And he was there in the flashing moment when the Florida War became inevitable. It’s fair to say Charley Emathla was the reason the war became inevitable.

So why don’t we know much about him? Today you can’t swing a cat in Florida without hitting a street, a park or a business named for the valiant Osceola. On Saturdays in the fall you’ll find tens of thousands of people sporting the name, image or likeness of Osceola on t-shirts and hats, some in warpaint, tomahawk-chopping their college football team to victory. But good luck finding Charley Emathla’s name on anything.1

It may be because Charley, in the end, was a leaver. He chose exit. Although we Americans are a nation of leavers, we rarely applaud the exiles. In our stories the heroes are the remainers and defenders, the martyrs and dead-enders. It’s harder to find glory in retreat.

It doesn’t help that we know almost nothing of Charley Emathla’s background, where he came from or who his people were. And the little that is printed on this score is wrong. (See bonus episode, coming soon.)

But it is worthwhile considering this remarkable man. It helps us understand the people who were becoming the Seminoles in 1835. And it exposes the sad trajectory of a war of ethnic removal, the kind still so common today.

Note: this post steps back in time before Osceola’s imprisonment in Chapter 6.

Maitland Meets Charley Emathla

First, let’s turn to Lt. William Maitland, U.S. Army. Perhaps William Maitland knew Charley Emathla on a handshake basis, but he certainly would have had a nodding familiarity with him. Before the war, American soldiers, Seminoles and black people mingled freely around Fort King. The federal Indian Agency operated there, handling the affairs of the reservation, and the fort’s sutler was a draw for trading goods from skins and sugar to ammunition and gunpowder.

How did Maitland view Charley? A good indication is found in the diary and letters of Pvt. John Bemrose — the English runaway turned American soldier. (See Chapter 2.) What Bemrose recorded, Maitland and other soldiers experienced.

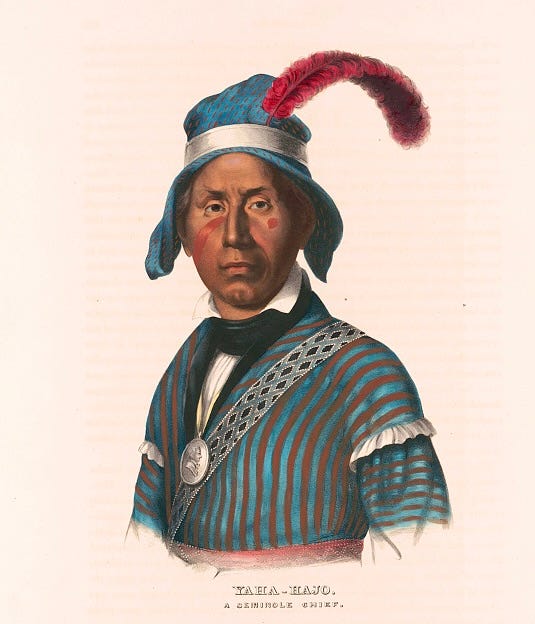

“Charlie Omathla . . . was a fine-looking and friendly Indian who was supposed to be very rich and enlightened. His dress and manner gave the impression of a substantial grazier [rancher], which I suppose he was, as he owned a large herd of cattle. He was frequently seen in camp [Fort King] and was the chief of a village nine miles from the fort called Omathla’s Town. He seemed a free and easy, very sociable man, who was received by General Clinch in his quarters as an old acquaintance. [In council] Charlie[’s]… speech was more genial than any of the other speakers. Except for the language he spoke, I could imagine that he was one of the settlers, so free and easy and so like a farming man.”

Charley struck another observer similarly. But we get a little more detail.

“[Charley Emathla] spoke a little English and this faculty with his amiable, sociable countenance and manners, made him an object of interest to all the garrison. He was about 50 years of age, and about 5 feet 11 inches high. His frame was large and muscular. In council he discovered more foresight and common sense than any other of the Chiefs.”

Common sense to the Americans meant Removal. When these observations were made in the spring and summer of 1835, Charley Emathla had undergone a change. For years he had opposed the American demand for Removal. But lately he had come to believe that emigration was the only way forward. The change was not made with enthusiasm but with bleak calculation — it was the less bad of two dismal options.

Charley’s reluctant conversion endeared him to the Americans. Like the rest of the officers, Maitland’s whole purpose at this rugged post on the edge of America’s frontier was to see the Seminoles out of the territory. So when a man of Charley Emathla’s stature turned and spoke in favor of Removal, the boys in blue paid close attention. Charley, now a “friendly chief,” was a welcome sight at Fort King.

But to Seminoles most committed to hold onto their land, like Osceola before his imprisonment, it was Charley’s stature that posed the greatest threat. When respected leaders began wavering, it threatened to tear the fabric of the fragile nation. If that happened, the remainers could not hope to beat the American Removal program.

Charley Emathla Had a Difficult Journey

Back on May 9, 1832, well before any Seminole agreed to Removal, Charley Emathla first walked into history. Along with many other head men that day he marked his “X” on the Treaty of Payne’s Landing. And he was one of seven “confidential chiefs” appointed to carry out the crucial triggering stipulation of that treaty. The delegation would travel to the part of the Arkansas territory that is today’s Oklahoma to examine the land that the U.S. offered to swap for the Seminoles’ Florida land. If the Seminoles were satisfied with it, then the terms of the Removal treaty would become binding. If not, the treaty would be null.

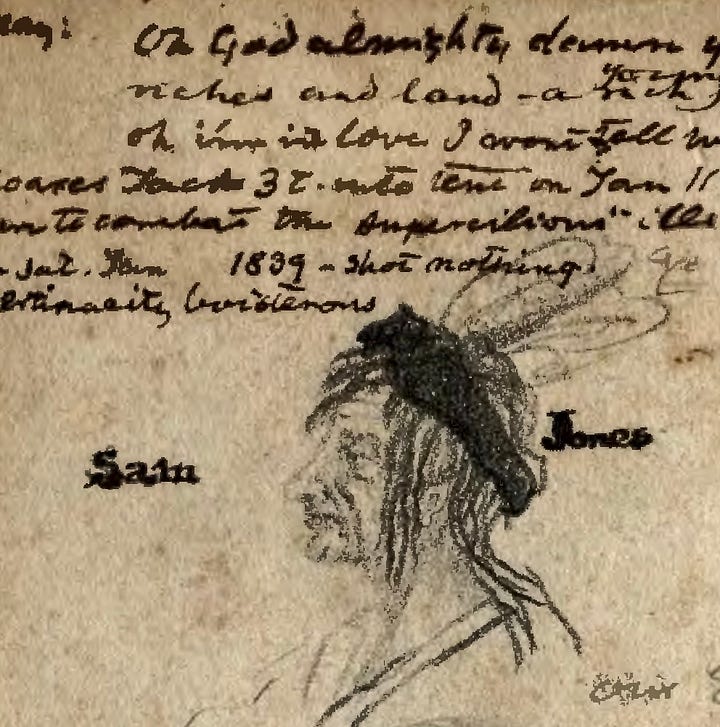

Charley and the six other head men, accompanied by “their faithful interpreter Abraham,” a black Seminole of signal importance, made the arduous scouting journey northwest to the Arkansas territory in the fall of 1832. There, American agents touted its qualities: a bit cold in winter but well watered, fine to farm and decent to hunt. The Seminoles didn’t disagree, but found the occupants violent and prone to horse theft, particularly the Pawnees and Cherokees.

Then the Americans turned the screws. They demanded the delegation mark a paper declaring that they, “on behalf of their nation,” approved the land and agreed to commence the Seminole Removal from Florida. Charley and the others, of course, refused. In the first place, they didn’t agree. But moreover, the idea that just seven men could speak for the entire Seminole nation was ludicrous. Each Seminole town spoke for itself. This Arkansas delegation was just a fact-finding team. They were to examine the country and report back to the people in Florida who would then, with the facts at hand and in grand council, consider whether to enact the Removal treaty of Payne’s Landing.

But with the seven head men isolated in Arkansas, the Americans wouldn’t relent. They reportedly plied the men with liquor, and when that didn’t work, they abused and threatened them. They told the Seminoles they wouldn’t return them to Florida unless they marked the paper. It got ugly. The men remained for months in wintertime Arkansas. Finally, Charley and the others relented and marked what the Americans hyped as the “Treaty of Fort Gibson” in March 1833. After the Americans got what they wanted, they returned the men home.

A Frank Exchange of Views

Then an interesting thing happened — nothing. It was another year and a half before the Americans pressed Removal. In that time, the Seminoles, having heard all about distant Arkansas, determined not to leave Florida. They gave no credence to the bogus Fort Gibson document and so, in their minds, the 1832 Treaty of Payne’s Landing was a dead letter.

The Americans saw it differently. In October 1834, after the year-and-a-half lull, a new U.S. Indian Agent named Wiley Thompson called his first conference with the Seminoles at Fort King. He had just a few simple questions for them: Did they prefer to be deported by land or by sea? Once in Arkansas (Oklahoma), would they “reunite” with their kinsmen the Creeks on the new reservation? Would they take cash for their Florida livestock or have the animals replaced in-kind out west?

The Seminoles found this puzzling. As Charley Emathla politely told Wiley Thompson:

“If we intended to go, then it would be proper the points be proposed to us should be decided upon. But why quarrel about dividing the hind quarter when we are not going to hunt? Why strain the water when you are not thirsty?”

One by one the top head men joined Charley Emathla. In calm tones, they explained to Wiley Thompson they weren’t interested in leaving their homes. They regarded the Payne’s Landing Treaty as moot and instead focused again and again on the Moultrie Creek Treaty which established the central Florida reservation.

Charley Emathla is the standout in the fascinating transcriptions of this three-day conference. (Versions can be found in Cohen, here, pp. 56-63, and Potter, here, pp. 50-66. For powerful clarity, read the description in the excellent Coacoochee’s Bones by Susan A. Miller, a member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma.) We can see the heavy responsibility Charley felt for his people. He recounted the difficult 1,000-mile journey to Arkansas by blue-water ship, flat-bottomed riverboat, horse and foot.

“I endured it because my nation might be benefitted by the result of the expedition; but how will not the women and children suffer in such a passage? When the men, the grown men and warriors, sunk, and their legs were as broken reeds. There were but few of us in the [Arkansas] deputation. We were ill used by the Agent [John Phagan]. We were abandoned when sick on the road…. If the few on that expedition were exposed to such hardships and ill-usage on their journey, how much more suffering must there be, when the whole nation is moving in a body? If the heart is not big enough for tens, how can it contain hundreds?”

(Charley’s caution was sadly borne out as hundreds were to die on the Seminole Trail of Tears.)

Charley’s Emathla’s diplomatic instincts are evident. He does not bluster or pose. In this first meeting with Wiley Thompson, he appeals to the Agent’s humanity.

“You have just come among us. You meet us in council now for the first time. Remain here with us, and be as a father to us, and let us be as your children. The relation of parent and child to each other, is peace — it is soft and sweet as arrow-root and honey.”

Wiley Thompson was not moved. True to form, he responded with insults and threats. He called the head men dishonest and singled out Micco-Nuppa as a straight-up liar. He told them they spoke like foolish children and were not deserving of their offices. Wiley noted that, as their greatest friend, he was bound to tell them this. If they would not remove voluntarily, the Americans would compel them to do so.

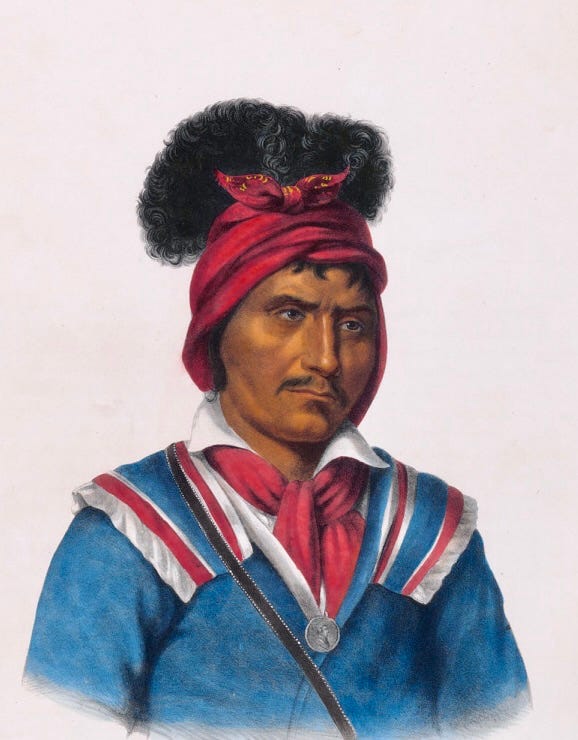

The Squeeze Begins

Over the course of the next year, the United States cranked up the pressure on the Seminoles. (See earlier posts here and here.) Wiley Thompson cut off trade in arms and powder and threatened to withhold the annuity. He hectored the Seminoles at two more conferences and disrated the tribal hierarchy. The U.S. President Andrew Jackson sent a long bellicose message to the Tribe. The U.S. Army built up its forces and capacity around the reservation at Fort King (Ocala) and Fort Brooke (Tampa).

Perhaps Charley Emathla and his people felt this pressure more keenly than others. Emathla’s town was at the northernmost border of the reservation. There, they would have experienced more conflict with white settlers and slavery’s bounty hunters than those deeper in Seminole country. Moreover, Charley’s town was perched midway between Fort King and its commanding officer’s sugar plantation, also called Fort Drane (see map at top). The neighbors all pressed for Removal.

At some point, it tipped for Charley. Although he foresaw misery and death on the trail of exile, he came to believe that staying and fighting for Florida would be even worse. By the late spring of 1835, Charley publicly endorsed emigration. He was not alone. Several other leaders — Holata Micco, Fokke Lusti Hadjo (Black Dirt), and Holata Emathla — also concluded it was the only hope for their people.

The summer and fall of 1835 saw the Seminoles increasingly torn over the Removal question. Most of the top leaders remained solid in their commitment to keep Florida. But an increasing minority, representing perhaps one-third of the nation, either favored emigration outright or kept pressing the Americans for better Removal terms before they would commit.2

This was the schism that the most ardent remainers feared. As they stockpiled lead and powder to stay and fight the Americans, men like Charley Emathla spoke of leaving. These were not leaders; they were traitors. They weakened the body and spirit of the nation, sapping the energy needed for armed resistance.

If the Seminole nation was to be saved, the traitors would have to be dealt with.

________________________

Next: Showdown at the Fort King Corral

References:

Randal Agostini, An Englishman in the Seminole War: A Memoir Based Upon the Letters of John Bemrose (Florida Historical Society, 2021).

Grant Foreman, Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1953, p. 328, quoting correspondence in Newbern Spectator, North Carolina, February 26, 1836, copied in Army and Navy Chronicle II, p. 197.

Susan A. Miller, Coacoochee’s Bones: A Seminole Saga, University Press of Kansas 2003.

Woodburne Potter, The War in Florida: Being an Exposition of its Causes and an Accurate History of the Campaigns of Generals Clinch, Gaines and Scott, Baltimore: Lewis & Coleman 1836.

I found his name on only one thing. Near the blinking caution light at the rural intersection of County Road 225 and State Road 326 in northwest Marion County, Florida, is an unincorporated and sparsely inhabited area called Emathla. Charley Emathla and his people lived here until late November 1835. It is horse country today.

Americans insisted that the exiled Seminoles live on the reservation already demarcated for the Creeks (Muskogees) in Arkansas (Oklahoma). The Americans reasoned that the Seminoles had split from the Creeks generations before and should reunite. The Seminoles strongly objected to this. In the late summer of 1835, several Seminole head men pressed the U.S. Indian Agent hard for their own reservation independent of the Creeks after Removal. This was based not just on the pure desire for self-governance, but on the fear that the Creeks, far more numerous than the Seminoles, would kidnap the Seminoles’ black enslaved people. Historically, a good number of blacks had escaped Creek masters in Georgia and Alabama and found refuge with the Seminoles. They became nominal “slaves” to the Seminoles though in a less injurious system. The Seminoles knew from experience that the Creeks hadn’t forgotten their claims on these people and their children.