Respect Due for Micco-Nuppa

Chapter 3: The Seminole leader deserves a second look

In the previous post, U.S. Indian Agent Wiley Thompson had convened the Seminole leadership in March 1835. As he exhorted them to leave their Florida home for lands in the Arkansas Territory (now Oklahoma) the talks collapsed, literally. A month later, talks resume…

Micco-Nuppa was a no-show.

Which should have surprised no one. In the annals of chief-to-chief diplomacy, no one consistently ghosted his dates like Micco-Nuppa. He was never rude about it; always sent delegates to give excuses. Often claimed illness.

Still, it rankled Wiley Thompson. How can a host ditch his own meeting? The whole point of agreeing to meet at the Seminole camp was to keep the micco from begging off as he’d done at the fort a month ago when the stage collapsed. Yet here they were, on the morning of April 23, 1835, Thompson and Gen. Duncan Clinch and a company of U.S. troops, which again would have included our Lt. Maitland, having marched the half mile from Fort King.

Fifteen hundred Seminoles were there, but not the one Wiley Thompson wanted. Thompson was pissed, and pissy. Where the hell is he?

The micco is off at his own camp several miles distant, Jumper said, waving in a direction that might have been east or just as easily west but in any case vague enough so no one could run off to fetch him. Sick. Belly ache. Real bad.

Thompson wanted Micco-Nuppa (Micanopy) because he embodied the crucial strain of the Seminole nation. The many bands loosely bound together in this nation fell mostly into one of three dominant groups: the Mikasukis (or Miccosukees), the Tallassees, and the Alachuas. But Alachuas held particular sway and Micco-Nuppa was their governor. A micco was the leader of a town or set of towns held together by personal and spiritual bonds. And Micco-Nuppa was the micco of miccos. Thompson knew that if Micco-Nuppa was absent from the talks, their importance was necessarily diminished. So did Micco-Nuppa.

Micco-Nuppa was of royal lineage. In the mid-1700s, Ahaya, a man from the Oconee Valley in Georgia, had begun the Florida dynasty when he carried the embers of his town’s sacred fire south to Payne’s Prairie, near today’s Gainesville. (See earlier post.) Ahaya, or Cowkeeper, called his new town Cuscowilla.

When Ahaya died in 1785, leadership fell to his able nephew Payne (a.k.a. King Payne), under whom the Alachuas prospered and spread. The Alachuas, like all Muskogees and the Apalachees and Timucuas before them, were a matrilineal society. Clan and inheritance came through the mother. Fathers were bystanders. So Ahaya’s office did not descend to his son but rather to his nephew, the son of his eldest sister. This makes some sense. One could never know with certainty the biological father of a child. But the mother was certain as were the mother’s brothers, the uncles. That’s where the family blood flowed. So uncles and nephews, determined in relation to the mother, had particular ties and obligations to each other.

Payne’s reign ended in 1812 as he was cut down in battle against adventuring Georgians. (More on this in a later post; Patriots!) The white invaders burned Cuscowilla and other Native and black towns on the Alachua plain. Leadership passed laterally to Payne’s brother, Boleck, a.k.a. Bowlegs, who settled his refugee Alachua people 40 miles west on the banks of the Suwannee River.

Again war came for the Alachuas. This time it was Andrew Jackson who rampaged through the Suwannee towns in 1818 driving the Alachuas, along with Mikasukis, Tallassees and allied blacks (collectively, the Seminoles) east and south into the peninsula of central Florida. This six-month spate of violence is called the First Seminole War.

It’s not clear when Bowlegs left us, but about this time Alachua leadership passed to his nephew, Micco-Nuppa. The micco was one of many Seminole head men to mark the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the United States. In it, the Seminoles exchanged their north Florida lands for a huge, though agriculturally poor, reservation encompassing central Florida.

Now, 12 years later in the spring of 1835, the United States had determined it couldn’t tolerate Indians in Florida after all. It was Agent Wiley Thompson’s job to run the Seminoles out. But without Micco-Nuppa to negotiate the terms, he was hamstrung. And angry.

Maybe he can come in a day or two, Jumper said. But he knew of Thompson’s trademark impatience. Tomorrow was no better than next year.

The Haters Club, or Misunderestimating the Man

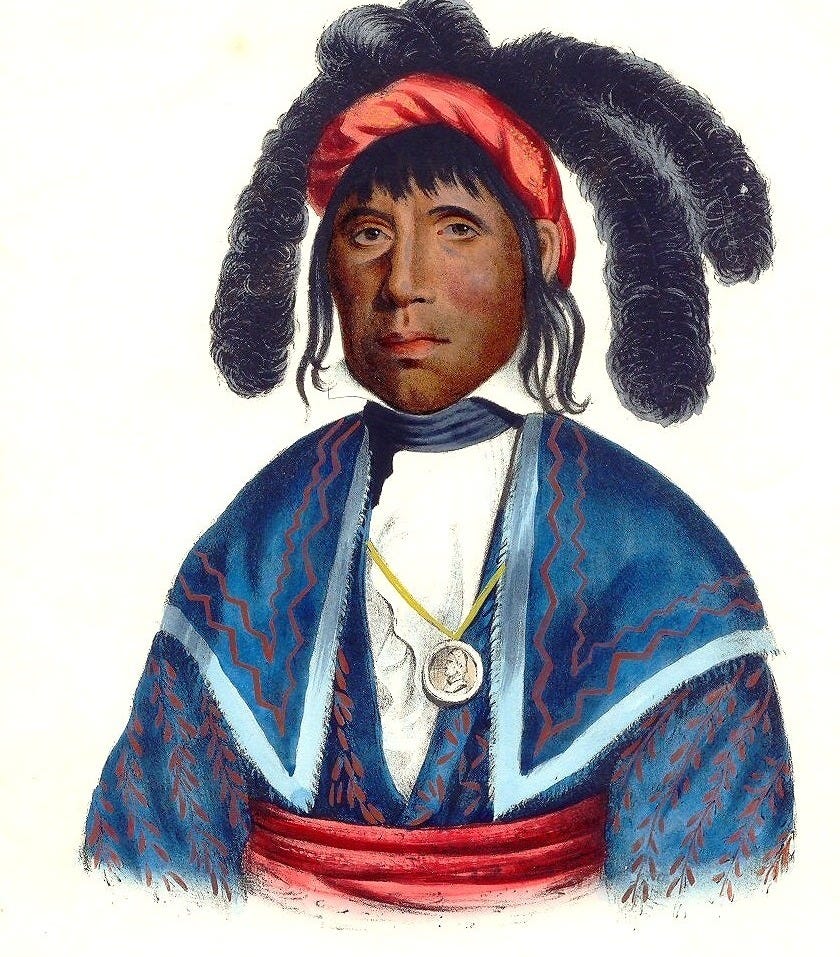

What galled Thompson all the more was the low esteem in which he held the Seminole leader. It was a view widely shared by whites. Micco-Nuppa was “a man of but little talent or energy of character,” in Gen. Clinch’s eyes. Another officer described the chief as five-foot-six, 250 pounds, “with a dull eye, rather a stupid countenance, a full fat face, and short neck.” Other observers began with his gluttony, moved on to his carbuncles, and were less charitable from there. He was indecisive, they said, his advisors led him by the nose. He was an indifferent oaf who only waddled onto the throne by virtue of high birth.

We can’t just blame racism because these same chroniclers often waxed poetic about the physical and moral majesty of other Native people. But Micco-Nuppa always came out fat, lazy and stupid. To the micco, American history has been unkind.

And I would say unfair. The man assumed his primacy in some of the most trying times of his emerging nation’s already difficult history and held his office through an unprecedented era of bloodshed, terror and dislocation — a tenure of some 30 years. That is not often the record of the dim and lethargic.

But Micco-Nuppa always came out fat, lazy and stupid. To the micco, American history has been unkind.

Perhaps his longevity is a testament to the tensile strength of the Seminoles’ intertwined logic of governance and cosmology. Some stations were assumed by heredity, others by merit. But in none was incompetence tolerated. A micco inherited hiliswa, a divine governing spirit. This is not unlike a British king or queen at the same time in history. Into Micco-Nuppa’s body was vested the soul of the nation. He held persuasive, though not autocratic, authority. For the Seminoles at a time when they might fragment under tremendous pressure, an enduring micco was required. One emerged, or at least the Seminoles worked with what they were given.

In the American records Micco-Nuppa is a cartoon figure. But we know some of his history and can reconstruct other parts from contemporary events.

Micco-Nuppa was born about 1780 in north Florida and would have been of prime fighting age, about 30, when conflict came to the Seminoles in earnest. Perhaps he was with his uncles Payne and Bowlegs as they fought the Patriots War (1811-12) from St. Augustine to Alachua. In 1813, he was surely with his people as they evacuated the Alachua plain forever ahead of a vengeful American army. It is not unlikely that he fought rearguard actions against Jackson’s army on the Suwannee in 1818. This is to say nothing of the intramural conflicts that surely arose as the Seminoles were corralled into the central Florida reservation under the terms of the 1823 Moultrie Creek Treaty.

So Micco-Nuppa knew plenty about war, but he also was schooled in diplomacy. In 1826, he had been part of a Seminole delegation to Washington, D.C. via Charleston and New York. It must have been mind-boggling for these travelers from the Florida sticks: cities crowded with high stone and brick buildings, streets teeming with white and black people jumping on and off wheeled carriages and trains, rivers surging with sail and steamship traffic. The might of this burgeoning American nation must have awed Micco-Nuppa and the others.

But it did not overwhelm them.

Micco-Nuppa and other head men sat down face-to-face with the U.S. President, John Quincy Adams, and his Secretary of War, James Barbour. The Seminole agenda was to get the U.S. to expand the central Florida reservation because it was too poor to sustain them. But the American agenda was to stop the Seminoles from harboring escaped slaves. The President also strongly recommended the Natives quit Florida altogether and migrate west to lands across the Mississippi River.

The Seminoles shrugged at the slave extradition request and told the President they weren’t going anywhere. As Micco-Nuppa later explained:

“Here my navel string was cut,” he said, “the earth drank the blood, which makes me love it. I was raised in th[is] country, and it if is a poor one, I love it, and do not wish to leave it.”

Micco-Nuppa and the Seminoles left Washington with a U.S. commitment, soon honored, to enlarge their reservation. In return, the Seminoles gave up nothing.

Micco-Nuppa was no dunce. Experience had given him the measure of American military power. He had some grip on diplomacy with whites and was a veteran of Native politics — the jostling for power, position, or just survival among the Mikasukis, Tallassees, and Alachuas. Perhaps Micco-Nuppa, who was settling into his mid-50s as America’s removal project came to a boil, was actually an astute politician masquerading behind a veil of indolence. He knew he was no orator so he left that to Jumper; for counsel regarding whites he relied on Abraham who, having once been enslaved by them, had insight. Perhaps Micco-Nuppa had developed the wisdom to know when the presence of the micco of miccos was really required.

Chiefs on a Roll

“Bah!” Wiley Thompson said, chalking the micco’s absence at the April 1835 conference up to a “shuffling disposition to shun responsibility.”

So a cranky Thompson started the conference without Micco-Nuppa (just as Micco-Nuppa wanted). Predictably, things went sideways. Day one was a continuous drone of each side speechifying, neither side being moved.

On the second day, Thompson turned the screws. He demanded the Seminole leadership mark their X’s on a paper attesting to the validity of the stale Payne’s Landing Treaty as well as the bogus follow-up “treaty” of Fort Gibson.1

The core Seminole leadership scoffed at this. By then they fully recognized the poison in the paper. Holata Micco declined. So did Abayaca and Coa Hadjo and Jumper. Further, Jumper said the absent Micco-Nuppa would have no interest, either.

Thompson spluttered. Outraged, he declared he would strike these five men from his “Chiefs” roll. No longer would the United States recognize them as the head men of the Seminole nation.

This was worse than the stage collapse at Fort King. These men constituted the top tier of the nation’s leaders. The allegedly defrocked head men must have been stunned at the stupidity of the action. For an American bureaucrat to think he had the power, with the stroke of a pen, to rearrange the hierarchy of the Seminole nation was beyond silly. But such was Thompson’s arrogance, or desperation.

When news of Thompson’s tantrum reached his superiors in Washington, D.C., the Agent was quickly reprimanded and told to walk it back. Even President Jackson disapproved. (You’ve gone way too far when Jackson disapproves.) The Seminole nation’s head men were, of course, its head men. That’s how diplomacy works. Each nation selects its own representatives.

At the end of the day, Thompson’s action only succeeded in driving the wedge deeper between the nations while cementing his own reputation for imperiousness. A trait that would come back to haunt him, as we’ll see.

But whose reputation wasn’t diminished by this conference? Who didn’t have to suffer firsthand the indignity of being insulted? Who may well have seen all this coming and so acted to spare his nation the dishonor of having the incumbent of its most sacred office publicly belittled?

Micco-Nuppa.

We really should reassess the man.

Next: Wiley can’t help himself.

Sources

Canter Brown, Jr., “The Florida Crisis of 1826-1827,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. LXXIII, No. 4 (April 1995).

George Catlin, The Boy’s Catlin: My Life Among the Indians, Charles Scribner’s Sons New York 1928.

Myer M. Cohen, Notices of Florida and the Campaigns, Charleston and New York 1836. Accessed at Internet Archive.

John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War 1835 - 1842, University of Florida Press 1967.

Susan A. Miller, Coacoochee’s Bones: A Seminole Saga, University Press of Kansas 2003.

Kenneth W. Porter, “The Cowkeeper Dynasty of the Seminole Nation,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXX, No. 4 (April 1952).

Woodburne Potter, The War in Florida, Being an Exposition of Its Causes and an Accurate History of the Campaigns of Generals Clinch, Gaines, and Scott, Baltimore 1836.

John T. Sprague, The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War, Forgotten Books 2012, originally published New York 1848.

Patricia R. Wickman, Osceola’s Legacy, University of Alabama Press 1991. Accessed at Internet Archive.

Historians have spilled buckets of ink and gigas of bytes debating the legalities and misunderstandings of the treaties. It’s interesting, but unproductive. When Congress handed Andrew Jackson the Removal Act in 1830, the wholesale deportation of the Seminoles was ordained, just as it was for all other Native peoples in the Southeastern U.S. including Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creeks. One must really torture the text and context of the Payne’s Landing and Fort Gibson treaties to conclude they amount to a fair agreement on the part of the Seminoles to give up their Florida home.

So fascinating. I am enjoying your insights. Super informative and interesting.