The Seminoles Won't Go

Chapter 4: America's Indian Removal project looks like a bust

In the previous post, Indian Agent Wiley Thompson, desperate to pry the Seminoles out of Florida, tried excommunicating Micco-Nuppa and the top Seminole leadership. The ploy failed. In the late spring of 1835, Thompson needed a miracle.

“[O]ne who has been more hostile to emigration and has thrown more embarrassments in my way than any other, came to my office and insulted me….”

— Wiley Thompson, June 3, 1835

The Indian Agent’s Dilemma

The whole ethnic cleansing thing wasn’t going well for the Indian Agent, Wiley Thompson.

His Washington bosses had given him an additional title — Superintendent of Removal — and expected him to have the Seminoles lined up to depart in the summer of 1835. Army logistics had already swung into action. They were arranging transports to ship thousands of Seminoles out of Tampa Bay across the Gulf to New Orleans, then up the Mississippi River to Arkansas. Government contractors were securing blankets, clothes, seed corn and farm tools to ease the exiles into the West.

The problem for Wiley Thompson, in the late spring of 1835, was that the top Seminole leaders had told him flatly, yet again, they weren’t going anywhere. Wiley had been at the Seminole Agency for a year and a half. In that time, he goaded the Seminoles, bullied them, cut off their supplies. He proclaimed demands directly from the U.S. Secretary of War and even U.S. President Andrew Jackson. He threatened military action. But still, the Seminoles weren’t going anywhere.

Which would make Wiley’s mission a failure. And Wiley wasn’t built to fail. He was a rigid, punctilious man known for getting results. But as summer neared, just three notable head men had agreed to emigrate with their people. The majority of the nation, and its top tier of leadership, remained firmly opposed.

So Wiley mailed excuses to his Washington superiors, he played for time. A summer departure was impossible for a dozen reasons, he wrote to the Secretary of War. But come winter, by God, he’d have the whole nation peacefully deported. Florida would be Indian-free by February 1836.

Wiley had no reason to believe this. In fact, there were growing rumblings of armed resistance from the younger warriors. And the Seminole head men who had agreed to emigrate also appealed to Wiley for protection because of death threats. The wheels of Indian Removal may have been spinning in Washington, but at the Seminole Agency where it counted, they were mired in the ditch. Wiley Thompson knew that barring some miracle, he would soon have to confess his humiliating failure to his bosses.

Then, one day in late May 1835, Wiley’s luck turned. A grim-faced Seminole man walked into his office demanding a meeting.

This would be no ordinary meeting. It altered the course of Wiley Thompson’s life. And this Seminole was no ordinary man.

He was Asin Yahola. Or Osceola. The soul of Seminole resistance.

Osceola - A Lifetime of War

At one time, Osceola was famous throughout the United States. He grew to be a darling of the national press in the 1830s and ‘40s. Cities and counties as far as Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin were named for him.

But today he is little known to us. His name conjures an angry painted warrior, maybe stabbing a football field with a flaming spear, goading college students into a frenzy. We shouldn’t entomb him in that amber. His story is more interesting.

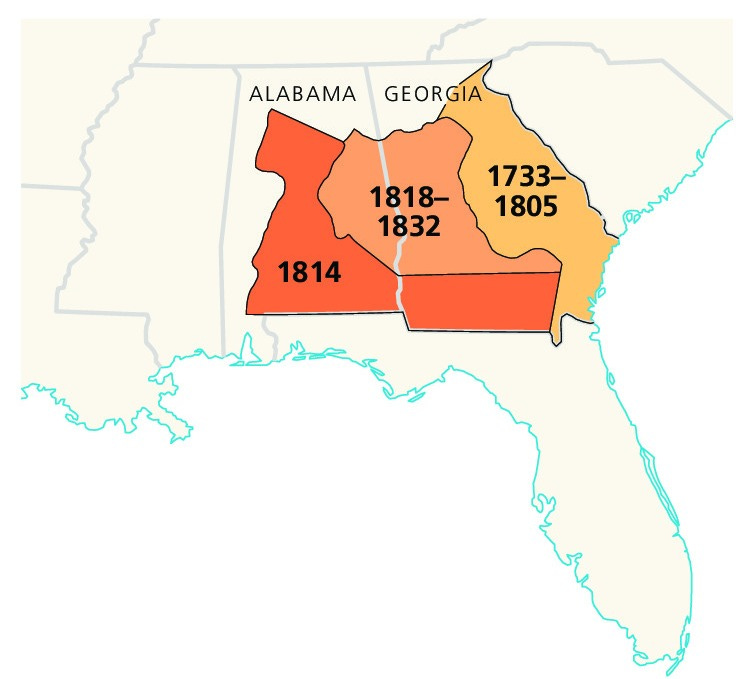

Osceola came to Florida as a war refugee, probably at about age 10 in 1814. Prior to this, he had grown up among his Creek family in Tallassee, near the Tallapoosa River in eastern Alabama. His family was part of a Nativist movement — the Red Sticks — who violently opposed those Creeks who accommodated white culture and trade. In 1813, this schism led to the Creek civil war. Alarmed at the Red Stick program, Major General Andrew Jackson came in on side of the “friendly” Creeks.

At the insanely bloody Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, an army of Jackson’s federal troops, with allied Creeks and Cherokees, decimated the last Red Stick stronghold. It is said that more Indian combatants died in that battle than any other in American history — some 800 to 1,000 on the Red Stick side alone. Those that weren’t killed in the desperate fight on the ground were shot as they tried to swim the Tallapoosa River. Surely young Osceola lost cousins, aunts and uncles there.

Horseshoe Bend broke the back of the Creek nation. In its wake, Jackson forced a treaty that took 22 million acres from the Creeks — about half of today’s Alabama and much of southern Georgia. Certainly hundreds and perhaps thousands of refugees, including Osceola’s family, were forced south and crossed the border into Spanish Florida.

Some settled among the Mikasuki people in the Tallahassee area. Some went further east to the Suwannee River towns where they joined the Alachuas and blacks, recently driven west from the Alachua plain (more on this in a later post). In both cases, the respite was short-lived. In 1818, Jackson and his Creek allies attacked these north Florida Seminole settlements in the so-called First Seminole War, pushing the survivors south and east into the Florida peninsula.

Osceola and his people finally found refuge in central Florida where he grew to adulthood. One can only imagine the impact these years of warfare and flight had on him — the humiliation, sorrow, fear, and anger.

But Osceola’s story wasn’t unique. It had become the common Seminole experience. What was so special about Osceola? He was not of noble blood or a prominent clan, so heredity didn’t advance him as it had Micco-Nuppa.

Osceola’s rise was a matter of talent and timing, plus, when the time came, a sure hand at cold-blooded killing.

Osceola Catches America’s Eye

Osceola enters the record in 1834 at Fort King when he was about 30 years old. If American observers uniformly dumped on Micco-Nuppa (see previous post), they mostly adored Osceola.

“In stature he is about at mediocrity, with an elastic and graceful movement; in his face he is good looking, with rather an effeminate smile; but of so peculiar a character, that the world may be ransacked over without finding another just like it.”1

Osceola was lighter-skinned than most Seminoles, owing perhaps to white ancestry (his father may have been an English trader named Powell), but his hair and eyes were jet black. There is broad agreement that Osceola was a good hunter and excellent ball player.

In 1834 and ’35, Osceola was a common sight around Fort King. Among the Seminoles, he had climbed in rank to Tustenuggee, a military leader, perhaps a kind of sheriff policing border disputes among his people and whites. In this capacity he often visited the fort on official business.

But Osceola also came just to hang out. Private Bemrose, the English runaway turned Army hospital steward, says Osceola struck up a particular friendship with a Lt. John Graham:

“They were daily seen with one another in the community. Both shared a strong love of field sports, and it was a very common sight to see both of them, returning to camp after a hunting expedition in the woods. Lieutenant Graham was a fine specimen of a man measuring 6 feet 5 inches tall, young, and doubtless very interesting to his Indian friend.”2

Our Lt. William Maitland, posted at Fort King, also would have been familiar with Osceola in those peaceful days. But just a few months later, Maitland would face Osceola in combat. Perhaps Maitland shared one of the starkly different views of two other men who also faced Osceola in war.

“In his character Osceola combines much of the gallantry, cool courage, and sagacity of the white man, with the ferocity, savage daring and subtlety of the Indian,” wrote one, a South Carolina Militia officer. “We recognize the proof of no ordinary intellect, but of a great mind, steady in the pursuit of its purpose, and, grasping, not vainly, but with energy, the proper means to obtain it.”3

But the other observer, an Army officer, wasn’t having it.

“[Osceola’s] talents are not above mediocre; and he was never known … to possess any of the nobler qualities which adorn the Indian character: all his dealings have been characterized by a low, sordid, and contracted spirit…. Perverse and obstinate in his disposition, he would frequently oppose measures to which it was the interest of his people that he should advocate.”4

This officer hoped his published “description of [Osceola] may perhaps serve to disabuse the public mind of the ‘noble character,’ ‘lofty bearing,’ ‘the high soul,’ ‘amazing powers’ and ‘magnanimity’ of the ‘Miccosukee chief.’”5

Love him or hate him, Osceola was charismatic. And worryingly for Wiley Thompson, Osceola was the prime agitator against the Removal project. As young rank-and-file warriors murmured about armed resistance, they found a voice in this rising war chief. And Osceola was increasingly influential with Micco-Nuppa and other head men.

“The sentiments of the nation have been expressed,” Osceola had admonished Wiley Thompson when the Agent threatened the head men with violent deportation. “There remains nothing worth words! If the hail rattles, let the flowers be crushed – the stately oak of the forest will lift its head to the sky and the storm, towering and unscathed.”6

Wiley Thompson’s Tough Love

Osceola’s portraits may vary, but Wiley Thompson’s is static. Fifty-three years old in 1835, Wiley was a stiff-necked Georgian from Elberton. A strict disciplinarian and able administrator, he was mission-driven to infuse the world with his own habits and ethics. He started his career as the commissioner of a boy’s academy, then climbed to the rank of Major General in the Georgia Militia before being elected to Congress. In Washington, he caught the eye of President Jackson who felt that Wiley was just the sort needed to remove of the Seminoles from Florida. Wiley took the job for $1,500 a year, plus expenses.

Wiley was the personification of America’s Indian Removal project. He was arrogant and relentless in his dealings with Seminoles. When Seminole leaders said they’d been manipulated into the bogus emigration treaties, Wiley mocked them as liars, old women or foolish children.

Then he lectured them about their future should they remain in Florida (which, he insisted, they could not). Their land would be sold to whites and white laws would govern them. When abused, they would have no recourse because American law would not hear evidence from non-whites. Without land to farm or hunt, Seminoles would be left to beg scraps from their white neighbors, vagabonds in their own home.

On this point, Wiley was not wrong. That specter had been playing out for Native people since the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. So Wiley pushed the Removal Act rationale that Indians could be saved only by emigrating west beyond the reach of admittedly avaricious and violent white settlers.

Of course, there was another option, an obvious one the Seminoles advocated and had a right to expect: the U.S. could respect the Seminoles’ right to remain on their treaty-protected Florida reservation and should patrol its borders to keep settlers, whisky traders and slave catchers out. It was as simple as it was just.

Wiley knew that would never happen. America’s goal was to take all Indian land east of the Mississippi. As a Congressman in 1830, Wiley Thompson had voted for the Removal Act. In 1835, as Indian Agent to the Seminoles, he positioned himself as their tough-love friend. Deportation, he told them, was for their own good.

Bad Day at the Office, or, Wiley Finds a Way

If Wiley Thompson’s singular purpose was to engineer the expulsion of the Seminoles, Osceola’s was to unify them against it. It was inevitable the two men would clash. And they had done so several times before Osceola rolled into Wiley’s office in late May 1835.

Maybe he brought an interpreter or maybe Cudjo was on hand to do the work. Osceola, looking at the four walls, chair and desk, must have wondered what compelled white people to spend their days in these little cells. Maybe it explained Wiley’s poor disposition.

Osceola was serious, perhaps angry. The accounts vary on what his business was. He had come to complain about white settlers abusing two Seminole men. Or about ill treatment of his wife. Or to upbraid the Agent for seizing his whiskey. Or to remind the Agent he was on Indian land and that white men’s days on it were numbered.

Wiley’s own account doesn’t tell us. He reports only that before it was over, Osceola “insulted me by some insolent remarks.”7

Osceola left to go on about his day.

Wiley sat in his office, face reddening. He emerged and quickly consulted a couple of Army officers who confirmed his impulse.

“I was fully satisfied the crisis had arrived,” Wiley wrote, “when it became indispensable to make an example of him.”8

Wiley Thompson passed the order to have Osceola arrested, chained, and thrown into confinement.

“Four of the soldiers of the garrison were detailed for that duty, and it was with difficulty they succeeded in overcoming him; they secured him about two hundred yards from the fort, amidst a shower of the bitterest imprecations upon Gen. Thompson, which he continued to utter in a perfect state of phrensy for some hours after he was secured.”9

In the Overreaction Olympics, Wiley Thompson was Usain Bolt, serial medalist. Jailing Osceola for disrespect was top-drawer, especially with American/Seminole relations as brittle as they were. But Wiley wasn’t done. A rare opportunity had fallen into his lap.

Wiley pondered the price he would exact for Osceola’s freedom. Played well, he figured, it could save his Removal mission and, not coincidentally, his reputation.

Osceola, confined in irons, was incandescent. But he soon mastered his anger and began calculating his next move, too. No one could have guessed it.

Next: The price of Osceola’s release.

_____________________________

Sources:

Randal J. Agostini, An Englishman in the Seminole War: A Memoir Based Upon the Letters of John Bemrose, Florida Historical Society Press 2021.

Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress: Thompson, Wiley (1781-1835), https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/T000222, accessed Oct. 12, 2024.

William Boyd, “Asi-Yaholo or Osceola,” Florida Historical Quarterly, No. XXXIII, Jan.-Apr. 1955.

George Catlin, Illustrations of the Manners, Customs & Conditions of the North American Indians with Letters and Notes, Vol. 2, London 1876, accessed at Internet Archive.

Charles H. Coe, “The Parentage of Osceola,” Florida Historical Quarterly, No. XXXIII, Jan.-Apr. 1955.

Document No. 271, House of Representatives, 24th Cong., 1st Sess.,“A supplemental report respecting the causes of the Seminole hostilities, and the measures taken to suppress them,” June 3, 1836.

Susan A. Miller, Coacoochee’s Bones: A Seminole Saga, University Press of Kansas 2003.

Woodburne Potter, The War in Florida: Being an Exposition of its Causes and an Accurate History of the Campaigns of Generals Clinch, Gaines and Scott, Baltimore: Lewis & Coleman 1836.

William Wragg Smith, Sketch of the Seminole War by an Officer of the Left Wing, Daniel J. Dowling, Charleston 1836.

Catlin at Letter No. 57.

Agostini at 93. Osceola’s intimacy with Lt. Graham was the subject of some contemporary speculation. One story had it that Lt. Graham either wed or doted on Osceola’s daughter. Another was that Graham later survived close battles because Osceola had instructed his men to avoid shooting him. Both were probably apocryphal.

Smith at 6, 7-8.

Potter at 11-12.

Id. Potter notes that Osceola was erroneously called a Miccosukee. Though Osceola came to be closely associated with Mikasukis in the war, he was a Muskogee-speaking Tallassee, an Upper Creek Town.

Miller at 37, citing Myer M. Cohen, Notices of Florida and the Campaigns, Charleston and New York 1836, at 62.

Letter from Wiley Thompson to Brigadier Gen. George Gibson, June 3, 1835. Doc. No. 271 at p. 197.

Id.

Potter at 86.

Wow! Super compelling!