White Flight: Evacuation of Sugar Country

Ch. 14: Hundreds are Liberated as Rumors of Seminole Attack Empty the Plantations of New Smyrna, Port Orange, Daytona and Ormond

Previously, in Chapter 13, the white residents of New Smyrna were in retreat. Fearing a Seminole attack, they had fled downriver in boats loaded with household goods and enslaved black people.

In the late afternoon, the boats fetched up on the eastern bank of the tidal Hillsboro River, under the shallow rise to Col. Dummett’s house.

It was a relief. For the whites, anyway. They had put distance between themselves and what they assumed was an incoming Seminole war party. At Dummett’s, on the all-but-deserted barrier island that shelters Florida’s east coast, they hoped to safely pass the night.

A slim quarter moon passed overhead as Christmas night deepened. The refugees could look straight back down a mile-long stretch of river to where it curved at New Smyrna’s waterfront. The black skyline was pancake flat except a lone hill whiskered in scrub oak and cabbage palm. This was an ancient shell midden, the work of the long-gone Timucua people. At the base of this hill stood the plantation manager’s house, which John and Jane Sheldon had abandoned just hours earlier.

In the distance a yellow light flickered, then grew. Soon it surpassed the modest limit of a campfire, then outstripped even a bonfire. It was a structure fire. The plantation house was engulfed in flame. Other buildings followed suit, set alight by the Seminoles. The sky over New Smyrna glowed brightly. John Sheldon later claimed he saw 100 Seminoles dancing before the flames.

The whites at Col. Dummett’s reconsidered the safety of their position. The Sheldons, Hunter, and Dummett hastily boarded their small boats and headed north. They left the black people behind with orders to follow in the cargo-laden lighters when the tide was favorable. Evidently, they thought this a reasonable demand.

Making their way up the river, the Sheldons — John, his wife Jane, and her mother — found a schooner anchored in the Mosquito Inlet (now Ponce Inlet) and clambered aboard. They rode out the night in the shadow of the newly constructed lighthouse that towered over the dunes on the south bank of the inlet. But the lighthouse sat dark. It had been waiting some time for its first shipment of sperm whale oil to fuel the lamp whose beams would be reflected out into the world by giant polished mirrors.

Probably just as well for the Sheldons who were not interested in being seen.

As daylight broke, John took his little boat back to Dummett’s to get the trunks which they had left in the care of the slaves. But John came upon an unexpected scene.

The black people were not, in fact, following as the whites had directed. Instead, they were rowing the lighters back toward the smoldering ashes of New Smyrna. They must have felt this was a more enticing option than rejoining their enslavers. But then John Sheldon witnessed something more alarming. The blacks were intercepted by eleven Seminoles arriving on a raft. The Seminoles then forced them back to the shore by Dummett’s house. There, the Indians commenced “breaking open the trunks and destroying the goods.”1

John Sheldon turned his boat and beat it back to the anchored schooner where he onboarded his wife and mother-in-law and fled up the coastal river.

The Sheldons had watched their lives as plantation managers evaporate in the smoky glow over New Smyrna the night before. Now they knew Seminoles raiders were in hot pursuit.

Refuge in the North

The Sheldons — like all sugar planters on Florida’s east coast — knew that the farther south they were from the gates of old St. Augustine the more precarious their position.

The Seminoles knew it, too. Which is surely why John Caesar and Emathla began their operations in New Smyrna. Some 70 miles from St. Augustine, it was the southernmost, and therefore most vulnerable, of the American settlements. Still, the Seminoles must have been surprised that all it took for complete victory were mere rumors of their presence. Their reputations indeed preceded them.

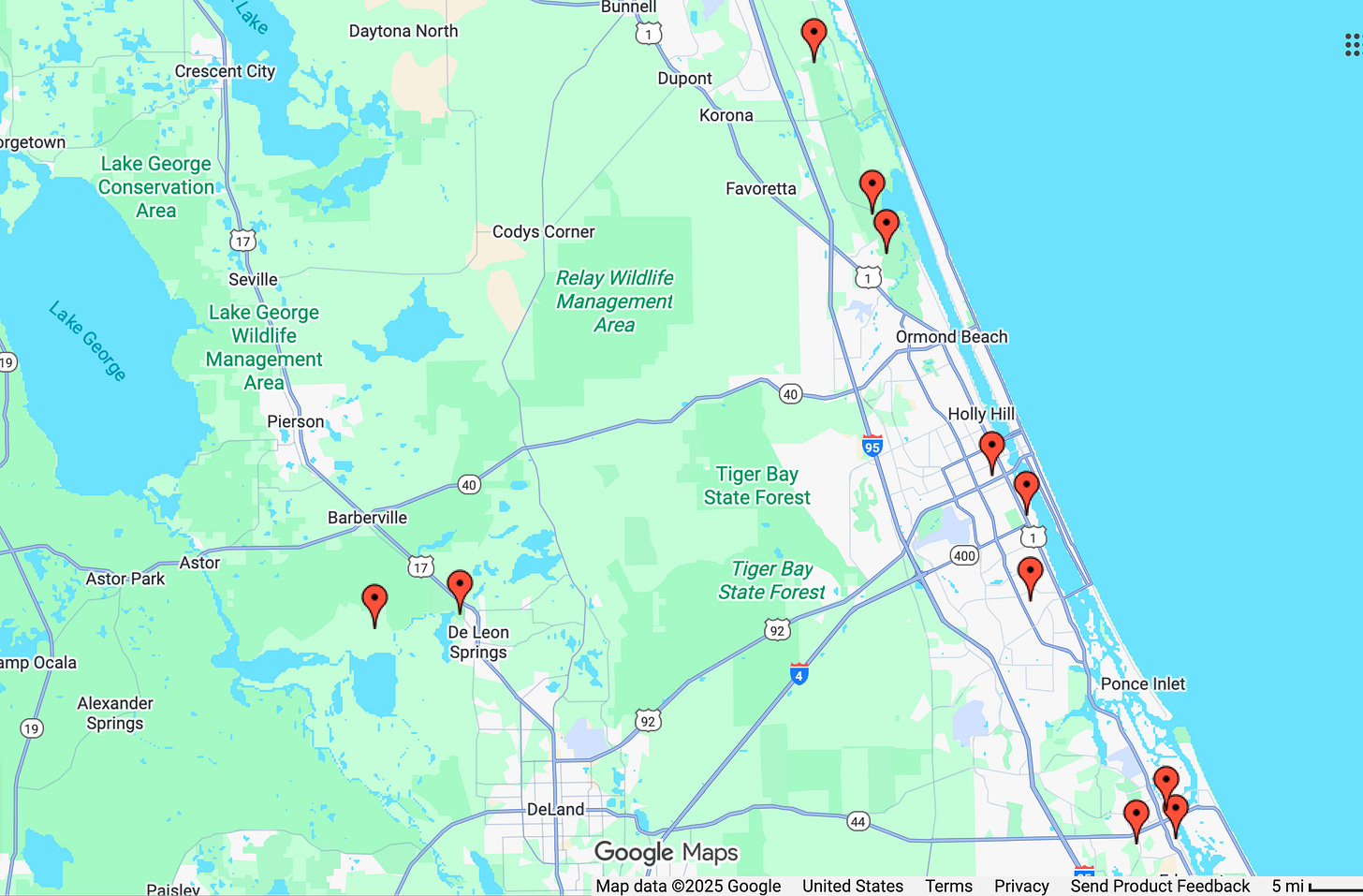

But the Seminoles did not linger in New Smyrna. They moved rapidly north, targeting every plantation along the way. In the week following Christmas 1835 they took, in turn, the Dunlawton plantation (in today’s Port Orange), Williams’s plantation (Daytona Beach), Heriot’s plantation (Daytona Beach), MaCrae’s plantation, a.k.a. Carrickfergus (Ormond Beach), and Dummett’s plantation, a.k.a. Darley’s or Rosetta (Ormond Beach). Seminoles also struck to the west along the St. Johns River, taking Rees’s Spring Garden plantation (DeLeon Springs in Deland), and Forrester’s (also Deland).

Still, as fast as the Seminoles moved, the white evacuees moved faster. They abandoned their homes throughout Mosquito (environs of New Smyrna) and Tomoka (roughly today’s Daytona and Ormond Beach). As Seminoles arrived expectantly in warpaint, they encountered not a shred of white resistance.

But there was a limit to this cakewalk. As we saw in the previous post, Brig. Gen. Joseph Hernandez at St. Augustine had anticipated trouble. A couple of weeks before Christmas he ordered a detachment of Florida militia south to protect the plantations. This detachment, under Maj. Benjamin Putnam (like Hernandez, a St. Augustine lawyer), stopped 30 miles short of New Smyrna.

Bulow’s Plantation Invaded by … Americans

Putnam chose the plantation of John J. Bulow as headquarters for his field operations. Located on a wide tidal creek, Bulowville was by far the largest of the coastal plantations. At its maximum extent, some 300 black people labored on its 2,200 acres of sugarcane, rice, cotton, corn and indigo. Bulow’s great sugar mill with soaring stone chimneys dwarfed any in the Mosquitoes.

Young bachelor Bulow, who had inherited the plantation from his father, was a difficult man. He protested angrily as Putnam commandeered his estate. It would ruin his cordial relations with the Seminoles, Bulow argued (correctly). Putnam persisted and, it is said, put the spluttering slavemaster under guard while troops seized his cotton bales, timber, and other materials and equipment to build an impromptu fortress around the big plantation house by Bulow Creek. In the crowning insult, Putnam and the militia officers dined at Bulow’s table by candlelight; Bulow was expelled to the yard.

In the days following Christmas 1835, Bulowville became not only a military garrison, but a sanctuary for all the whites fleeing north from Mosquito and Tomoka. This included the Sheldons, Hunter and Dummett, who came ashore at Bulow’s, fearful of traveling on to St. Augustine without guards. The plantation became very crowded and provisions were limited. Some officers quartered in the slave cabins that formed a wide semicircle around Bulow’s plantation house which backed up to the creek.

Hundreds Liberated from Slavery

Whether these militia men displaced the inhabitants is not clear. Bulow may have sent some or all of the black people from his plantation north for safekeeping at St. Augustine. Several slaveholders from Mosquito and Tomoka had done so and more would soon. Anastasia Island, within the protection zone of St. Augustine, quickly became a sprawling camp of enslaved black refugees.

But for many other black people, the chaos of Christmastime 1835 had severed their ties to American slaveholders. By the end of December, roughly 330 had either joined the Seminoles or were on their own in the Florida wilderness. This slave liberation (to be discussed in a future post) was of a magnitude far, far greater than any in American history prior to the Civil War.

Meanwhile at Bulowville, the Florida militia and plantation evacuees hunkered down to wait for the almost-certain onslaught of the Seminoles who were sweeping north with numbers augmented by newly recruited black warriors from the burned plantations.

This was Mary Sheldon’s description long after the fact. But it seems unlikely the Seminoles would destroy valuable plunder.